Kalesnikoff Mass Timber chief operating officer Chris Kalesnikoff inside the company’s mass timber plant in South Slocan. Photo by David Carrigg /PNG

CASTLEGAR — Tall and tanned, Chris Kalesnikoff stands in the baking sun looking over a big parcel of bare land beside the Castlegar airport.

There’s not much to see now – just an expanse of dirt covered in excavator tracks with gravel piles, water tanks and reinforced concrete cylinders scattered about.

But by the end of the year, this site — about four city blocks in size — will be transformed into a bustling 80,000-square-foot assembly plant for prefabricated mass timber buildings, thanks in part to $6.7 million from the provincial government.

“We started as a forestry company, then a sawmill, then mass timber. And, now, with prefabricated mass timber buildings, we are in construction,” says Kalesnikoff, chief operating officer of Kalesnikoff Lumber.

If this Castlegar site represents the future of the company, its sprawling 130,000-square-foot mass-timber production facility 20 minutes away in South Slocan represents how far it has come.

Earlier in the day, Kalesnikoff, 39, took the elevated walkway from one end of the pristine, machine-filled building — roughly the size of eight Olympic ice hockey rinks — to the other, showing off how lumber is transformed into glue-laminated beams (a.k.a. glulam) and cross-laminated timber panels strong enough to serve as floors, walls, ceilings and structural support beams.

Called mass timber, these new products are being used in place of concrete and steel, and are able to be built in a factory and then assembled on a construction site.

Kalesnikoff pointed to several glulam beams that will be used in The Hive, a 10-storey wood-construction office building going up in Vancouver’s False Creek flats.

Recently, the company was contracted to build a three-storey, 120-unit modular housing project in Montana.

At the other end of the facility, a dozen workers put the finishing touches on eight self-contained modules that include windows, carpeting, toilets and showers — with robotic technology used to cut spaces in the cross-laminated timber panels for things like electrical wiring and plumbing.

Since 2019, the company’s workforce has grown from 170 to 360, with an additional 100 workers needed for the airport facility when it is completed in December.

This means by next year the company will be injecting close to $2 million a month in wages into the local economy.

It has been a remarkable past five years for Kalesnikoff Lumber. The company that started as a traditional sawmill evolved into a manufacturing plant that produced musical soundboards, then into a mass-timber production facility during the COVID-19 pandemic, and soon into a first-of-a-kind mass-timber module-assembly plant in Castlegar.

Kalesnikoff is especially proud that the South Slocan facility is about to go 24/7, creating even more jobs for people living in West Kootenays. He is grateful that the provincial government is making a concerted effort to promote and encourage the mass-timber sector.

But there is an elephant in the room.

The state of the province’s wood supply is simply “horrible,” says Kalesnikoff.

Kalesnikoff Lumber is in a better position than most, because it is able to use wood sourced from its own sawmill. However, even wood supply at the sawmill is on the downturn.

“Right now, about 40 per cent of the lumber we produce at our sawmill gets consumed and turned into mass timber,” he says.

“Our current (sawmill) production has been on a slow and steady decline over the past five years and we expect that to continue to constrain our ability to actually grow our mass timber offerings. We ourselves are struggling to gain access to fibre even though we are creating the products that the government is promoting and says will help reshape the forestry industry. The two don’t align.”

Blood, sweat and tears through four generations

In 1922, the Kalesnikoff family arrived in the Kootenays after spending a decade in Saskatchewan.

There the parents raised three boys — Koozma, Sam and Peter. In 1939, the family purchased logging rights to the China Creek area south of Castlegar and set about building a road using horses, axes and muscle.

By 1940, the Kalesnikoff brothers had established a sawmill in the area that met a growing demand for cut lumber driven in part by the Second World War.

After moving the sawmill from timber lot to timber lot, the company settled in 1972 on a site in the community of Thrums on the Kootenay River between Castlegar and Nelson.

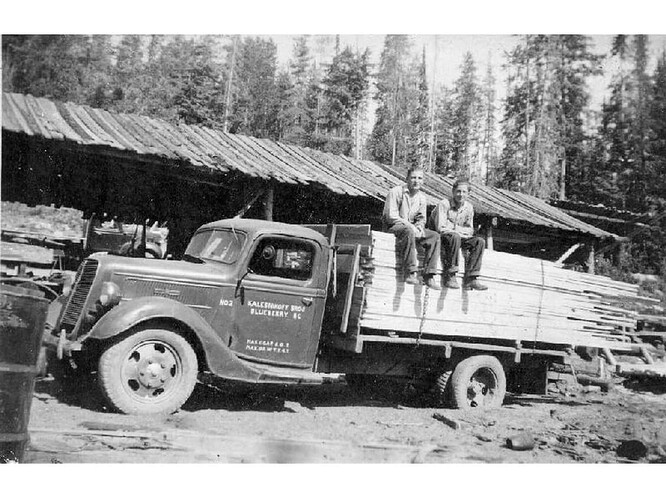

Kalesnikoff Lumber co-founder Pete Kalesnikoff (left) sits atop a company truck near Castlegar in the early 1940s. Photo by Kalesnikoff Lumber /sun

Over the years, control of the company fell into brother Peter’s hands (as Koozma had no children). He, in turn, handed the business over to his son Peter Jr., who learned from the ground up and was CEO until a year before he died in 2006.

Peter Jr.’s son Ken, who had been working at the sawmill since he was 14, took over and he remains president and CEO, with his son Chris serving as chief operating officer and his daughter, Krystle Seed, as chief financial officer.

Chris Kalesnikoff says he and his sister worked at the sawmill from a young age but were encouraged to go to university to get solid financial training.

Kalesnikoff studied commerce at Queen’s University, while Seed went to the University of Victoria and is a certified management accountant.

Between the two of them, with oversight from their dad, they have transformed a company twisting at the whims of the market into a Canadian leader in mass timber and prefabricated mass timber buildings.

“We are the only company in North America building modular structures out of mass timber,” Kalesnikoff says.

It was Ken who made the first move toward change in 1999 when he bought the South Slocan site, with a rough plan to start adding value to the raw wood products the mill was producing.

On this site, the company started Kootenay Innovative Wood.

“We essentially took the lumber from our sawmill and created new products with it. We started up doing some music wood soundboard and then got into lineal products. So we were doing softwood flooring, panelling and siding primarily,” Chris Kalesnikoff says. “It went OK, but most of our market was in the U.S. and we ended up getting beat up pretty bad by tariffs on softwood lumber.”

Around 2015, the company began looking at mass timber. The term mass timber was coined about a decade ago as the wood industry began developing engineered wood (basically wood and glue and wood joints) that was strong enough to support structural loads for large buildings in the same way steel and concrete does.

Over the next two years, Kalesnikoff travelled around Europe — including Italy, Austria, Germany, France and Denmark — visiting mass timber facilities and equipment manufacturers, noting that many were intergenerational businesses that made Kalesnikoff Lumber’s own four generations seem short-lived.

Seed spent that time working on financing and deciding how viable the project was economically.

By 2018, the family had decided it would move into mass timber.

“We leveraged everything because we saw where the lumber industry was headed. We knew we had to be different,” says Kalesnikoff.

“When we decided to invest in our mass timber plant. it was a matter of survival for us because we couldn’t see the long term road map of success for our sawmill. At that point, we had been in business for 85 years and my sister and I represented a new generation and it was a struggle to see how we could continue to grow,” says the father of three.

“We took on a huge risk to take on this facility. We broke ground in February 2019. It was one of those cold Februaries where you couldn’t punch through the frost it was so frozen.”

In the spring of 2020, the first product came out of the plant and by the end of the 2020 it was in full production.

“COVID was extremely challenging because we were commissioning the plant with European equipment and a lot of our technicians had to go back home,” he says.

“For the corporation, though, it was relatively important because it did strengthen the sawmill side of our business for two years when lumber spiked and that really helped as the mass-timber plant was being commissioned and getting its feet under itself.”

Kalesnikoff Lumber Co. Ltd. chief operating officer Chris Kalesnikoff stands at the site of the company’s new mass timber assembly facility being built in Castlegar. Photo by David Carrigg /sun

Another matter of timing that has significantly helped the business is the provincial government’s push to encourage use of mass timber, including direct financial support through B.C.’s manufacturing jobs fund to help pay for new facilities like the one in Castlegar.

Just last month, through the same fund, the government announced a $7-million grant for expansion of the Mercer Mass Timber plant in Penticton.

Province goes all in on mass timber

To say the provincial government has gone all in on mass timber would be an understatement.

The mass timber plan was released in 2022 and over the past two years there have been updates from the Ministry of Housing, the Ministry of Jobs, Economic Development and Innovation, the Ministry of Trade, the Ministry of State for Sustainable Forestry Innovation, and the Ministry of Forests.

There is also the mass-timber demonstration program, which is helping fund the construction of buildings using mass timber or mass timber-hybrid.

In April, Housing Minister Ravi Kahlon announced the B.C. building code had been amended to increase the allowable height of a mass timber building to 18 storeys from 12 storeys for residential and office buildings and to permit expanded mass timber use in school, library and care home construction.

Under the new building code, the mass timber is surrounded by fire-resistant material that delays the exposure of the wood structure to a fire.

Kahlon said the increase in allowable building heights for mass timber residential buildings coincided with new provincial zoning laws that allow buildings from between eight and 20 storey buildings to be erected close to transit hubs — depending how close they are to the hub.

According to a report on the state of mass timber in Canada, there are 20 completed residential mass-timber buildings in B.C. and 10 under construction.

Of those under construction, five are receiving funding from the mass-timber demonstration program, and will create close to 1,000 units of housing over the next four years.

Of Kalesnikoff’s largest mass timber projects underway, three are multi-family residential, two are student housing, one is a museum (the Royal B.C. Museum collections and archives building) and four are commercial.

Four are in Vancouver and the rest are in Victoria, Toronto, Utah, Seattle, Dallas and Portland.

With its new sales office in Vancouver and the modular mass timber assembly plant in Castlegar expected to be online in December, there will be no shortage of demand for Kalesnikoff’s mass timber products.

Supply of wood, however, remains a problem.

“Supply is a very dynamic situation across the province right now,” Kalesnikoff says.

“From our business perspective, we are excited to see the government continue to pursue and promote mass timber. At the same time, that product does come from the forestry side of our business and that side of our business is very constrained.

Forest tenure system needs complete overhaul, says UBC professor

Ninety-five per cent of B.C.’s 550,000 square kilometres of forest is under provincial control. Of that, 140,000 square kilometres are protected and around 2,000 square kilometres are harvested annually.

In May, Vancouver Sun columnist Vaughn Palmer reported that the B.C. NDP government’s efforts to improve access to fibre had failed.

This came after Canfor suspended its plan to build a $200-million state-of-the-art sawmill in Houston in northwestern B.C. due, the company said, to a shortage of timber and fibre compounded by government policies and regulations.

Canfor has been in business for 85 years, the same as Kalesnikoff Lumber.

“Unfortunately, while our province has a sufficient supply of timber available for harvest, the actual harvest level has declined dramatically. In 2023, the actual harvest was 42 per cent lower than the allowable cut, a level not seen since the 1960s,” Canfor boss Don Kayne said at the time, acknowledging that part of the problem was due to beetle infestations and wildfires.

“It is also the result of the cumulative impact of policy changes and increased regulatory complexity. These choices and changes have hampered our ability to consistently access enough economic fibre to support our manufacturing facilities and forced the closure or curtailment of many forest sector operations.”

The B.C. timber harvest fell to 47.7 million cubic metres from 71.1 million cubic metres between 2013 and 2022.

Gary Bull, professor emeritus at UBC’s department of forest resources management, says there are discussions underway among the provincial government, forestry companies and First Nations over the future of tenure management in B.C.

“We need serious reform of forest tenure and the new system must allow new participants and must have First Nations as managers or co-manager,” he said, noting many high-calibre forest executives are being recruited to work for First Nations forestry companies.

“In 2024, the issue is government reluctance to issue cutting permits because they are in discussions with First Nations who are ultimately going to control most of the tenure systems in B.C.”

Forests Minister Bruce Ralston says the government wants to make B.C. an international leader in mass-timber manufacturing, and praised the work of Kalesnikoff and Mercer.

“I am determined to continue promoting the expansion of this important industry and committed to supporting its access to fibre and lumber,” Ralston said.

“The mass-timber industry provides a market for sawmill lumber, creates local jobs and delivers housing for people. Forestry communities and British Columbians get the most benefit from every tree harvested, in exchange for a small proportion of the available timber supply.

“We are also exploring the use of alternative species to expand the basket of economically available wood. Research is already underway to unlock the potential of hemlock, (and) alder and other hardwoods, and our B.C. companies are leading the way by incorporating hemlock into their mass timber products.”

For Kalesnikoff, the company is committed to growth, but needs improvements in wood supply.

“We have been pedal to the metal,” he says.

“But maybe, now it’s time to take a breath and not get too far over our skis.”

Kalesnikoff Lumber Co. Ltd. chief operating officer Chris Kalesnikoff in the office of the company’s mass timber facility in South Slocan. Photo by David Carrigg /sun

Source: How a B.C. family pivoted to in-demand mass timber construction | Vancouver Sun