By David Elstone

The pandemic years of 2020 to 2022 created unprecedented market distortions. The following analysis uses the fabled lumber super cycle as context for looking into the future. Undoubtedly, this distortion’s influence will reverberate in business plans and models for years to come…

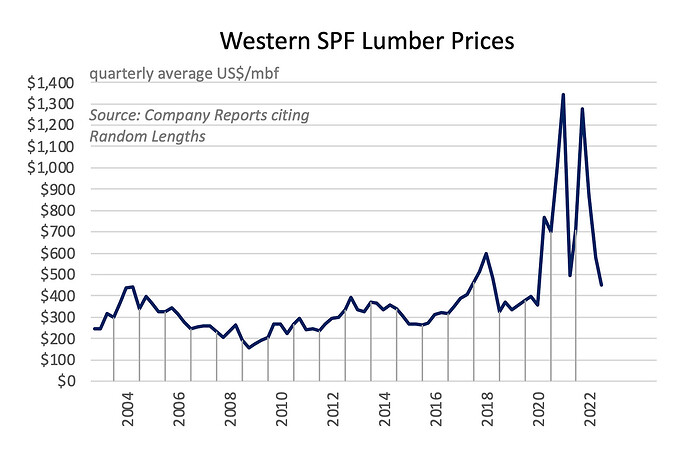

Are lumber prices with highs of US$1,300 per thousand board feet (on a quarterly average basis) going to be part of the new normal for North American lumber markets?

For the ten years prior to 2017, quarterly lumber prices averaged just below US$300/mbf. From 2020 to 2022 period, lumber prices averaged ~US$740, well above their pre-2017-decade average!

Today, weekly SPF lumber prices are said to be US$400 or below [depending on source]. Given lumber prices are still above their historical average, we must now be in the fabled lumber price “super cycle”?

The initial premise of a lumber price super cycle arose over a decade ago. At that time, anticipated lumber supply reductions (largely from British Columbia) would run headlong into seemingly insatiable Chinese demand and a strong recovery in US residential construction. The consequence would be lumber prices well above historical highs and sawmill profits would follow.

While current lumber prices are still strong in comparison to pre-2017 levels, they are regarded as near-bottom today after declining from their high point earlier this year.

SUPER CYCLE CHECK IN

To help understand this situation, let’s review the status of the conditions once cited as pre-requisites for the super cycle:

CHINA: When the super cycle concept was first put forward, BC lumber exports volumes to China were on the rise. That export business became critical to absorbing lower grade lumber produced from salvaged mountain pine beetle-killed timber. However, China’s influence has since faded as salvage efforts have come to an end and exports to China have declined. The current export business to China is no longer seen as a major diversion of lumber supply away from North America.

US RESIDENTIAL HOUSING CONSTRUCTION: Following their near vertical drop, It took over a decade for US housing starts to revert to their 50-year average of 1.4 million units. Since bottoming out in 2010, total starts reached a peak in 2021 at 1.601 million units. US starts are anticipated to decline in 2022 to 1.553 million units.

With US interest rates for fixed rate 30-year mortgages at their highest since 2002, the upward momentum in the US housing market has clearly slowed and is changing direction. Hopefully we are not going to experience the same interest rate - inflation roller coaster ride of the 1970s or 1980s. On the positive side, the sub-prime mortgage fiasco that drove the Great Recession in 2007 is not an issue today.

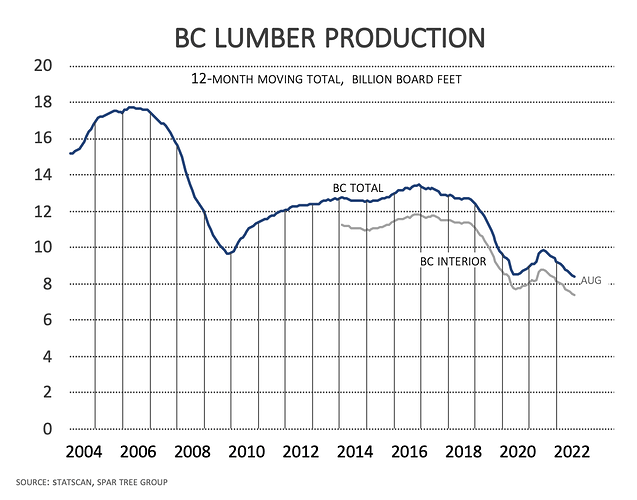

BC LUMBER PRODUCTION: Projected decreases to lumber productions from BC, with little capacity additions elsewhere in North America (at that time) combined with a recovery in US housing starts was the original premise for the super cycle as proposed by Russ Taylor. From 2017 to today, BC lumber production declined 35% or 4.4 billion board feet – much of which was anticipated as a result of the beetle, but not all. This reduction has meant BC’s US market share has shrunk from 16% in 2017 to a mere 9% today.

While BC production has decreased, other regions have since filled much of the gap in US lumber supply, most notably the US South and to some extent, European imports.

Given how these underlying conditions for the super cycle have evolved, I would not characterize the last three years as part of a super cycle. Rather, from 2020 onwards the world’s supply chains have all faced unique hurdles and demand has shifted in unforeseen ways because of the Covid pandemic.

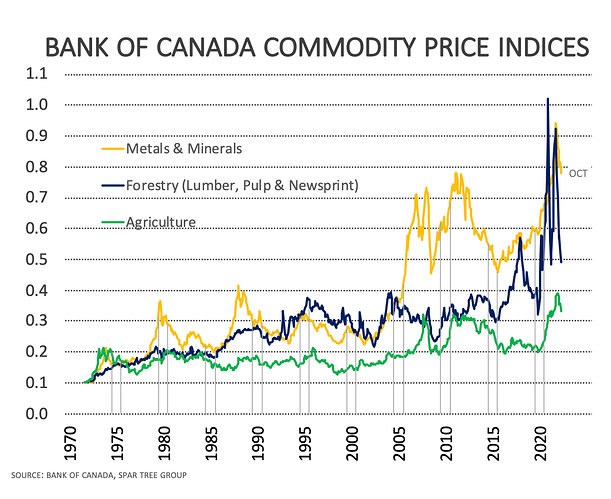

Lumber price appreciation during this time was accompanied by price spikes at a scale well above historical norms for other commodities like metals, minerals, and agriculture. Therefore, it may be argued that the 2020 to 2022 period was a “one-off” distortion due to the pandemic (and in part, due to transportation network issues), not entirely driven by the super-cycle conditions discussed here.

COSTS – THE AFTERPARTY HANGOVER…

Lumber producers’ cost structures have risen with higher lumber prices. Eventually though, lumber prices do fall and as a result, harvesting operations and sawmills are curtailing across the province.

Recently, Western Forest Products (on the BC Coast) announced a six-month curtailment of its APD sawmill and Skeena Sawmills (in Terrace) announced an operating rate of 50% for an indefinite period. That’s in addition to reduced production levels at interior sawmills operated by Canfor, West Fraser and Interfor.

[Since publishing the original article in the View From The Stump newsletter in late November, Western Forest Products has announced a temporary reduction to production spread across its BC manufacturing platform, removing 20 million board feet. Production will resume hopefully in January 2023.

Also, Canfor announced temporary reductions in production at its BC and Alberta solid wood facilities, removing 150 million board feet throughout December and January. Furthermore, Canfor “anticipates that the majority of its BC facilities will operate below full capacity in the New Year.” Don Kayne, President and CEO sums it up succinctly “due to the significant decrease in demand for solid wood products and challenging economic conditions, we are temporarily curtailing production in Canada.” Media reports say that the Plateau sawmill in Vanderhoof, BC will be shut down (in terms of no lumber being processed) for four weeks, and reportedly the Polar (Bear Lake, BC) and Houston, BC sawmills will be shut for three weeks.

Unfortunately, more curtailments are expected by others.]

Stumpage in British Columbia generally follows lumber prices but with a distinct lag. Currently stumpage rates for both the coast and interior regions are still at painfully high levels, in sharp contrast to lumber prices. It is the lagged volatility in stumpage that is driving sawmills throughout the province to curtail logging until stumpage becomes more affordable, which is likely to start in Q1 2023, but more clearly evident in Q2 given Q4 2022 lumber prices.

Higher costs influence the economically available log supply. The higher stumpage (and other costs), the less economical that log supply becomes. In addition, just finding timber has become harder due to biotic and abiotic influences on timber supply (i.e., beetle and wildfire) and because of the NDP government’s various policy changes (old growth deferrals and ensuing reductions to BCTS etc.).

Stronger markets helped sawmills with less economical log supply to continue operating. Unfortunately, higher log costs do not mean automatically higher lumber prices. If conditions for profitability do not improve in 2023, expect more market related closures.

To answer the original question posed for this article, are lumber prices with extreme highs expected to be part of the new normal for the North American market? It is hard to say for certain, but given the influence of the pandemic which appears to have now passed, I would say no.

However, nor do I believe that lumber prices are going back to pre-2017 average levels given the higher cost structure of the industry and relative changes in North America’s lumber supply and demand dynamics. While prices are not expected to reach the extreme highs of the last couple of years, it is probably fair to expect generally higher average prices than experienced pre-2017. As for the current cycle for lumber, it’s called a “boom-and-bust” cycle. At least that’s what I see from my view from the stump.