Balsam fir needles can kill ticks that cause Lyme disease, Dalhousie researcher finds

New study concludes oil in balsam fir needles is effective in preventing ticks from surviving winter

CBC News · Posted: Aug 18, 2022 7:32 PM AT

The balsam fir needles were found to be very effective in killing the ticks during winter. (Amal El Nabbout)

When Nova Scotia scientist Shelley Adamo noticed ticks avoid balsam fir trees, her professional instincts kicked in.

Adamo, a professor in the department of psychology and neuroscience at Dalhousie University in Halifax, said she noticed ticks often didn’t survive winter on her South Shore property which has thick stands of balsam fir trees.

Adamo said she had a “realistic hunch” that she should study the effects of balsam fir trees on Ixodes scapularis, the blacklegged tick that is a vector for Lyme disease. First discovered in Lyme, Conn., in the 1970s Lyme disease is now a common tick-borne disease that can cause fever, joint pain, rash and other longer-lasting effects.

The results of a three-year study into how balsam fir needles could help control tick populations was published on July 29 in Scientific Reports. Adamo spoke to Emma Smith of CBC Radio’s Mainstreet NS about what she discovered.

This is a condensed version of their conversation that has been edited for clarity and length.

Mainstreet NS10:03N.S. researchers investigate promising natural way to kill ticks that cause Lyme disease

Researchers at Dalhousie University have discovered that balsam fir needles can kill blacklegged ticks during the winter, preventing them from surviving until spring. Mainstreet’s Emma Smith speaks with Shelley Adamo about the study.

What did you do to determine that these balsam fir needles could could kill blacklegged ticks?

We tested them by collecting ticks and then we would put them in incubators and give them like a winter kind of experience.

We put them in tubes and then we put the balsam fir in with them and they died.

Then we tried it outdoors as well. So we worked with people at the Harrison Lewis Centre who were very good to us. They’re down in the Port Joli area between Liverpool and Shelburne, a real hotspot for Lyme.

We collected the ticks locally so we weren’t adding ticks at least, and we put them in their own little tubes so they couldn’t get out. But it was mesh so that snow and rain could fall in.

We put them in the tubes with balsam fir and put them out in December and collected them in March and we looked to see who lived and who died.

Some ticks got a little layer of oak and maple leaves, which is what they like. And some of them got a layer of of balsam fir. The ones that got to live with the balsam fir needles died. Pretty much all of them.

This could be a natural-product way to try to reduce the load of these potentially Lyme carrying ticks.

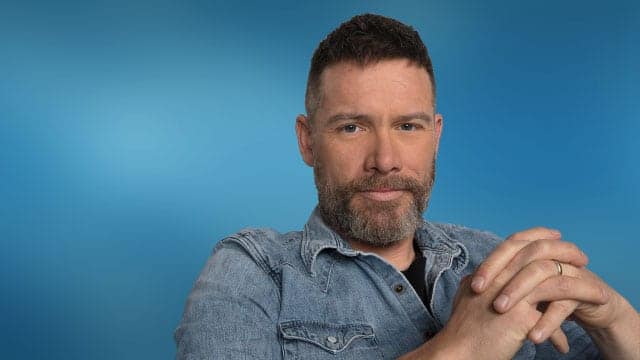

Shelley Adamo is a professor in the department of psychology and neuroscience at Dalhousie University (Shelley Adamo)

When you collected those tubes in the spring, the ones that had the maple and oak leaves, were those tick still alive?

They don’t all live. But surprisingly for ticks that evolved much further south, they actually can survive fairly well in in our Nova Scotian winters.

We vary quite a bit from year to year but our survival in the maple and oak was sometimes 60 per cent, sometimes 80 per cent, whereas the survival in the balsam fir was basically zero.

How big was your sample size of ticks? How many ticks were in these little tubes?

We did this over three winters. You want to make sure that this is reliable and repeatable, right?

We want to make sure that it’s rigorous.

Over three years we had hundreds of ticks.

We are quite confident of our results, particularly because they were so striking. Literally, the ticks die.

Can you tell me why you wanted to do these experiments in cold temperatures?

It seemed to me there was something about the cold weather and the balsam fir together that really brought out the tick-killing abilities of those balsam fir needles. That was one reason.

The other reason is I think winter is an overlooked season for controlling of ticks.

-

Lyme infection rate is 40 per cent in blacklegged ticks in parts of N.S., says researcher

-

Don’t throw away that deer tick. Researchers at Mount Allison want to study it

Most of our insects and ticks tend to overwinter in the leaf litter or just under the soil where it’s a bit warmer.

Obviously, there’s no food for them. So it’s a very stressful time. And that means it’s a time of opportunity to get rid of them because they’re already under stress. It might not take much to push them over the edge.

I thought maybe it would be easier to kill them in the winter than other seasons.

The other reason I wanted to focus on winter is that, you know, we’re worried about our pollinators and we’re worried about our beneficial insects. So you want to try to find a method of control that’s going to have minimal collateral damage.

By using something in the winter at least we know that we’re not going to be hitting flying pollinators.

Were you able to determine what’s in these balsam fir needles that’s killing the ticks?

We found that we could kill those ticks just by using the essential oils from these balsam fir needles.

Nicoletta Faraone who’s at Acadia University is my collaborator on this and her name is on the paper.

She managed to extract the essential oils from the needles.

We just added it to some cotton balls and we put them with a tick instead of balsam fir needles and, sure enough, that also killed them.

How long did it take to kill the ticks?

The needles themselves will do the job, but it takes a few weeks actually.

The essential oil can do it in a week, several days. Sometimes as short as three or four depends a little bit on the temperature. It works best at colder temperatures.

Have you found any downsides yet or do you expect to to find any downsides?

I hate to say it but there’s just no such thing as a silver bullet. Unfortunately, I suspect that we will. But we haven’t found one yet. We have been looking.