Key takeaways:

- New biomass power plants continue to come online in Japan, requiring an ever-greater quantity of imported fuel. The government’s feed-in tariff scheme, which has been tweaked but not canceled, incentivized these projects.

- Although understanding of forest biomass’s negative environmental and climate impacts is growing in Japan, policy advocates say operators of existing biomass power plants need to pay back construction bank loans, and the government’s refusal to admit its mistake is keeping biomass plants running.

- A major biomass fuel type is wood pellets, which in Japan is presently primarily sourced from plantation forests in Vietnam and primary forests in British Columbia, Canada. While BC ecologists have spoken out against wood pellets, and found allies in Vietnam, the biomass issue has proved challenging for Japan’s forest advocates.

- Though historically a small source of wood pellets for Japan, the growing popularity in Indonesia of pellets for both export and domestic use risks tropical forests there being cleared to make way for biomass energy plantations, NGOs warn.

Japan is at a crossroads in its controversial use of burning forest biomass to make electricity. While the government and private sector’s understanding of the fuel’s harmful environmental and climate impacts is growing, biomass power plants long in the pipeline continue to come online, requiring ever-greater volumes of imported wood pellets from primary forests in Canada or plantations in Vietnam.

Biomass importers and users in Japan are being forced to reevaluate their supply chains after U.S. wood pellet producer Enviva declared bankruptcy in March and prominent ecologists visiting Japan from Canada warned of the pellets’ environmental risks. In addition, new biomass policies from Japan’s biggest banks emphasize the importance of sustainable sourcing, which forest advocates say they hope will encourage biomass users to improve their practices.

But ultimately, forest advocates argue that, no matter which supply chain biomass users choose, burning wood to generate electricity is fundamentally untenable, as it puts significant amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere despite the global need to drastically reduce emissions.

In 2022, burning biomass accounted for roughly 6% of Japan’s total CO2 emissions, according to a Japanese climate expert. Still, under international carbon accounting rules, Japan is able to count biomass emissions as zero because trees sequester CO2 throughout their lives. Many experts say this is a misguided policy.

Using forest biomass for electricity generation took off in Japan in 2012, when the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry introduced a feed-in tariff (FIT) with 20-year fixed rates to support renewable energy projects.

“Before the FIT, we had basically no biomass power,” said Sayoko Iinuma, a member of the Japanese NGO Global Environmental Forum. “It began because the government gave it the green light.”

As of June 2022, the FIT had approved 7.6 million kilowatts of woody biomass capacity, although only 3 million kW has come online to date. When the FIT began in 2012, Japan imported just 72,000 metric tons of wood pellets, which are made by grinding up wood from forests or tree plantations. By 2023, that figure had jumped to 5.8 million metric tons.

In fact, the government, heeding the latest science and calls from biomass policy advocates, altered its FIT scheme in 2018 to effectively end the financial incentive for new biomass projects; plants now coming online have been in the pipeline for years.

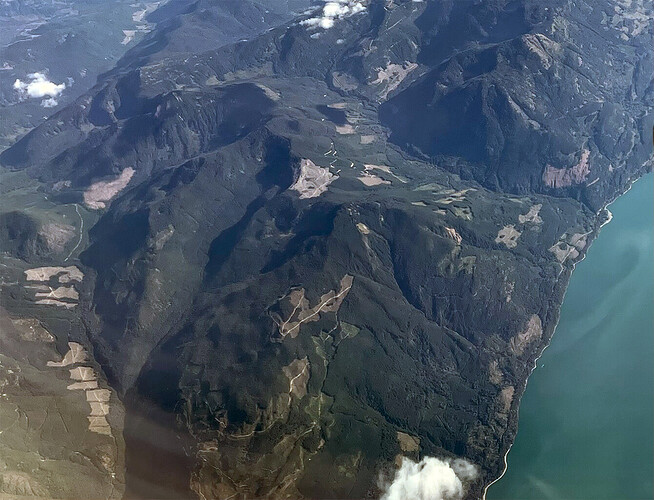

Clearcut forests in British Columbia, Canada. Image by Annelise Giseburt.

The Sendai-Gamo Biomass Power Project at Sendai Shiogama Port in Japan. Image courtesy of Mighty Earth.

‘Interest and curiosity’: Understanding Japan’s BC pellet supply chain

Today, Japan’s largest source of wood pellets, at 45%, is from tree plantations in Vietnam. However, its second-largest source, at 27%, is from old-growth forests in the Canadian province of British Columbia. From 2014 to 2023, Canadian pellet exports to Japan rose from roughly 62,000 metric tons to 1.7 million metric tons. Japan also burns biomass from other sources, such as palm kernel shells.

Increasingly, forest advocates in Japan and BC have been collaborating to better understand both sides of this supply chain.

In May 2024, Suzanne Simard, a professor at the University of British Columbia, and Rachel Holt, head of BC-based Veridian Ecological Consulting, visited Japan to speak about the unsustainable forestry practices behind BC wood pellets.

At a public event, Simard told attendees that almost all logging in BC involves clear-cutting previously untouched, primary forest.

Wood pellet proponents say that roughly 80% of BC pellet feedstock is sawmill residue, with the remainder coming from whole trees. However, Simard emphasized that even “waste” material like sawmill residue originates from primary forest. “When evaluating source of pellets, it’s important to know that … the method of logging isn’t sustainable,” she said.

Although BC requires clear-cut forest to be replanted, Simard pointed out that second-generation, monoculture forests don’t store as much carbon as primary forests, nor support the same level of biodiversity.

For Roger Smith, Japan director for the climate nonprofit Mighty Earth, Simard and Holt’s visit “felt like a turning point” on woody biomass in Japan.

“I think we are at a new stage of acceptance regarding the problems with biomass,” he said, noting a lack of pushback against Simard and Holt’s message. “There was real interest and curiosity in … why [BC is] allowing truly precious old-growth forests to end up as various products, including wood pellets.”

Reflecting on her discussions with people in Japan, Holt told Mongabay, “I was impressed at people’s knowledge of the issues around biomass … but then therefore [puzzled] as to why it’s being considered as a climate-friendly strategy.”

A similar gap between understanding and action can be seen in BC. Although a 2020 report by independent foresters calling for a “paradigm shift” in forest management sparked plenty of conversation, change on the ground has so far been limited, Holt said.

Despite this widespread desire for change, wood pellets for export are “a new segment of the [forestry] industry in BC, and it’s taking off at rapid speed with no controls over it,” she added. Large-scale subsidies like Japan’s FIT system “can push people to make poor decisions,” Holt said.

In addition to greenhouse gases, burning biomass also emits air pollutants, potentially impacting nearby communities, although total pollutants are regulated by Japanese law.

In May 2024, Suzanne Simard, a professor at the University of British Columbia, and Rachel Holt, head of BC-based Veridian Ecological Consulting, visited Japan to speak about the unsustainable forestry practices behind BC wood pellets. Image courtesy of Mighty Earth.

Ishinomaki Hibarino Biomass Power Project in Japan. Image courtesy of Mighty Earth.

Shifting supply chains: From North America to Southeast Asia?

Japan’s wood pellet supply chains have been shaken by the world’s largest wood pellet producer, Enviva, declaring bankruptcy in March 2024. Enviva, whose pellet plants are located in the U.S. Southeast, expected Asian, especially Japanese, customers to make up 45% of its business by 2025, according to company documents, and it was expanding operations to meet customer demand prior to its financial woes.

U.K.-based competitor Drax, with pellet mills in the U.S. Southeast and BC, could be in a position to fill that gap. Although Drax didn’t respond to Mongabay’s request for an interview with its Tokyo office, a company spokesperson said by email that biomass is “playing an important role in decarbonizing Japan’s energy system whilst keeping the lights on” and that using Canadian biomass “is supporting both healthier forests and the indigenous people who live there.”

However, Smith said he’s skeptical about Drax’s capacity for growth in BC. “Their overall forestry industry is in a pretty steep decline at present,” he said. Nearly half of BC’s sawmills have shuttered since 2005 as the province’s supply of economically viable timber falls, in part due to forests being hit by record fires and pine beetle outbreaks, both linked to climate change. Drax aims to open pellet mills in the U.S. states of California and Washington, but is facing opposition.

That makes it likely Japan will import even more wood pellets from Vietnam, Iinuma said.

Vietnam exported more than 2.8 million metric tons of wood pellets to Japan in 2023. Because Vietnam’s pellets are sourced from monoculture plantations — leaving primary forests, in theory, untouched — the Vietnamese supply chain could be seen as less reputationally risky compared with pollution concerns in the U.S. Southeast and unsustainable logging practices in BC, Iinuma said.

In May 2024, Vietnam’s Department of Forestry concluded a memorandum of understanding with Japan’s Forestry Agency to contribute “to achieving carbon neutrality by promoting sustainable forest management and effective use of forest resources,” a move Iinuma said is intended to strengthen Japan’s wood pellet supply.

However, Iinuma, who visited Vietnam this past April, said she worries the industry still doesn’t have sufficient oversight.

“They have few NGOs doing policy advocacy” on this issue, she said, adding that it’s difficult for Japan-based advocates to find on-the-ground forest activisits in Vietnam. Iinuma also highlighted risks associated with short-cycle plantation forestry, including worsening soil health and displacement of farmers in competition for land. Despite these risks, Japanese wood pellet demand incentivizes further development of Vietnam’s plantations.

Japan may also boost pellet imports from other Southeast Asian nations. One country of particular concern for forest advocates is Indonesia, which plans to cut on-paper carbon emissions at 52 of its coal plants by co-firing coal with a 5-10% mix of biomass. This would necessitate converting millions of hectares of primary forest into tree plantations. Expanding pellet production for export would put further pressure on Indonesia’s primary forests, which have already been hammered by logging, monoculture plantations and oil palm agribusiness.

Although Japan’s pellet imports from Indonesia have historically been small, they hit a record monthly high of 60,000 metric tons in March 2024, according to an industry publication. Indonesian media recently reported that the country’s 2023 wood pellet exports to Japan increased in value by 45% compared with 2022.

In April, Mongabay Indonesia, citing the NGOs Forest Watch Indonesia and Walhi, reported that Indonesian primary forest is being cleared for tree plantations for wood pellet production. Smith’s organization, Mighty Earth, has warned of the same. The region in question exports pellets to both Japan and South Korea, according to Mongabay’s report.

Clearcut forests in British Columbia, Canada. Image by Annelise Giseburt.

Japan’s government reluctant to admit a mistake

In early 2024, three of Japan’s biggest banks — Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group (SMFG), Mizuho and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group — released sustainability policies limiting support for new biomass projects. SMFG, which set the strongest policy of the three, said it will no longer support projects that use fuel sourced from primary forests.

Smith said he hopes Japanese companies importing and burning woody biomass follow the banks’ example.

“They have seen the bank policies, they have heard the latest science, they have heard the reality from British Columbia — what are they going to do about it?” he said. “The movement by the Japanese banks is the first step in the creation of a new consensus that not all biomass is equal and not all biomass is worthy of support.”

Indeed, a small but growing number of Japanese companies engaged in biomass-related business appear to understand that biomass’s smokestack emissions aren’t really zero. In a 2024 survey by Japanese NGOs, eight out of 18 companies, compared to three the year before, answered that biogenic carbon (i.e. smokestack) emissions were relevant for their organization.

After the feed-in tariff ended financial incentives for biomass in 2018, forest advocates now face the challenge of convincing operators and government officials to cancel pipeline projects and retire operating plants.

“Thanks to the FIT system, many operators find themselves having built these big power plants that can’t run without imported wood. The operators took out loans to build these plants, so unless the plants produce electricity, the operators can’t pay the banks back, and being unable to return the loans risks bankruptcy,” Iinuma said.

One possible solution, she said, would be for the government to buy out biomass power plants, similar to how Germany is compensating power producers to exit coal. Unfortunately, Iinuma said, a buyout would, “from METI’s perspective, be admitting that they made a mistake … and that’s something the government doesn’t want to do.”

Instead, METI has repeatedly tweaked the existing system, for example, adding a life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions reporting requirement in 2023. However, there’s little evidence to suggest that these add-ons are limiting biomass power expansion: Biomass constituted 5.7% of Japan’s 2023 energy mix, already beyond the government’s 5% target for 2030.

“Biomass is creating a carbon problem that the Japanese government is going to need to solve sooner or later,” Smith said, emphasizing that Japan has declared it will achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. “Because no matter how you count the emissions, they are never going to be near zero.”

Source: Biomass power grows in Japan despite new understanding of climate risks