The tariff drama as President Trump enters his second term of office has occupied much of the energy of financial markets and business leaders.

The 25% levies on all goods from Canada and Mexico implemented on March 4 are sending ripple effects throughout the entire forest products industry, given the level of industry integration and co-dependency on both sides of the border. While those seem to have been lifted for most goods as of March 7, it is anyone’s guess how the chaos will proceed from here. More disruption potentially awaits as President Trump has launched new trade investigations specifically into imported forest products from not just Canada, but other countries across the world.

While the market tries to process what’s to come on the trade front, it’s abundantly clear that the new administration is paying special attention to lumber and likely other wood products as it looks to craft trade policy. A series of statements from President Trump emphasize this focus and have caught the attention of the forest products industry and national media. For example, at the World Economic Forum on January 23, President Trump said, “We don’t need [Canada] to make our cars, we make a lot of them, we don’t need their lumber because we have our own forests… we don’t need their oil and gas, we have more than anybody.”

Follow-up comments from Trump and his surrogates have also emphasized the point of view that the US has the underlying resources to produce all its own lumber and wood product needs. In response, there have been a number of news articles highlighting the statements and questioning the idea of whether or not America can quickly and completely wean itself off Canadian wood products.

Filling the void of Canadian supply

First and foremost, it’s important to quantify the existing wood product supply flowing from Canada into the US market. In 2024, Canada accounted for essentially a quarter of US softwood consumption and about 20% of structural panel demand. On its face, that’s a massive gap to fill in a short period of time.

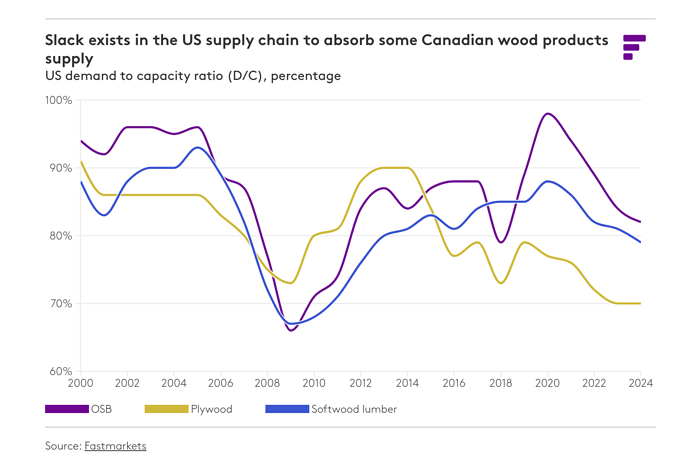

So, how well is the US capacity base positioned to meet this chunk of supply? Using softwood lumber as an example, in 2024 industry operating rates averaged 79%. Market conditions have been soft and at a cursory glance, there appears to be substantial slack in the supply chain.

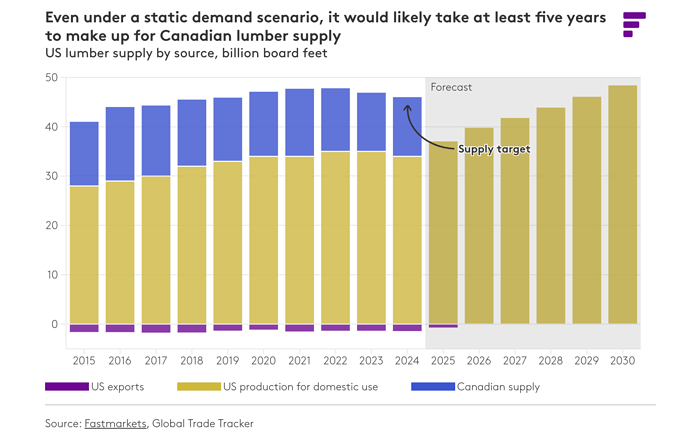

Assuming a 95% operating rate as a full utilization target — seasonal production trends and maintenance downtime makes sustainable output any higher very difficult — and knowing that US softwood sawmill capacity was around 47 BBF in 2024, that implies about 7.5 BBF of surplus capacity.

That is a sizable amount slack to be absorbed and room for production to rise in the US; however, Canada currently supplies about 12.0 BBF of softwood lumber to the US market. After accounting for the 1.3 BBF of exports the US has shipped in recent years, the US is still short just over 3.2 BBF of operable capacity to quickly fill Canadian lumber supply and still meet current demand levels. In other words, at current demand levels, the US softwood lumber market does not clear without Canadian supply.

So, we can definitively say that in the short run, the US sawmill industry lacks the existing capacity to fill existing Canadian supply. But what if we stretch the time horizon out somewhat to give more opportunity for the US supply side to expand?

US sawmills could add second and/or third shifts to existing operations to eke out more production if prices and profitability warranted. These sorts of “squishy” additions to capacity, while feasible, are still ultimately restricted by labor availability. Mill operators in rural markets will be the first to tell you that finding reliable workers just to keep existing production levels is a constant challenge for their business. The law of diminishing returns also applies to adding shifts, as sawmills will eventually be bound by technical bottlenecks like planing or kiln-drying capacity. It’s plausible that the US could increase supply this way, but as basic economics teaches, there’s only so much upside to raising production by adding labor to the existing capital stock.

Tariff it and investment will come … maybe

What about building new sawmill capacity? One advantage of building new, state-of-the-art operations is that these investments mitigate labor needs mentioned above through automation. We’ve seen this in a very tangible way in the US South over the last 10 years. But even here, the timeframe for getting a greenfield or brownfield sawmill investment from planning stages to hitting full technical capacity is usually a minimum of three years. This is assuming no permitting or technical delays, which is also a generous assumption given the limited sawmill equipment suppliers and normal delays that arise with these large-scale projects. So, even in favorable conditions, we are talking three to four years to build out the 3-4 BBF of sawmill capacity needed to replace Canadian supply.

These greenfield investments also come at a cost and are not without risk. Today, a 200-MMBF-per-year greenfield project typically runs about $150-200 million. To fill a 3-4 BBF capacity shortfall would require billions of dollars of capital investment to permanently replace Canadian supply. Will mill operators make this kind of additional investment in the US based on the assumption of further tariff barriers on Canadian supply?

There’s certainly a case that “reshoring” of manufacturing capacity would be a potential positive development for the US from the aggressive trade barriers being proposed and implemented by the current administration. However, these investments would only happen if market participants firmly believed large tariffs would stay in place over a long enough period of time to generate a positive return on investment.

Currently, tariffs are being used as a negotiating stick to address other Trump policy issues, most notably fentanyl and immigration. However, there’s also discussion of more permanent tariffs being used as a source of revenue to offset the effect on the federal budget deficit of potentially forthcoming tax cuts. Clearly, these two goals are at odds with each other and uncertainty around the future tariff policy of the US will remain high.

Without a firm expectation that tariffs will remain in place long enough for new capacity investments to pencil out, it is unlikely that any of the tariffs currently being discussed will lead to a massive influx of domestic investment in wood products or other manufacturing. This is one of the many limitations of using tariffs to drive industrial revitalization for any country, especially solely through the executive branch’s authority.

The rise of SYP: A tariff story or a fiber story?

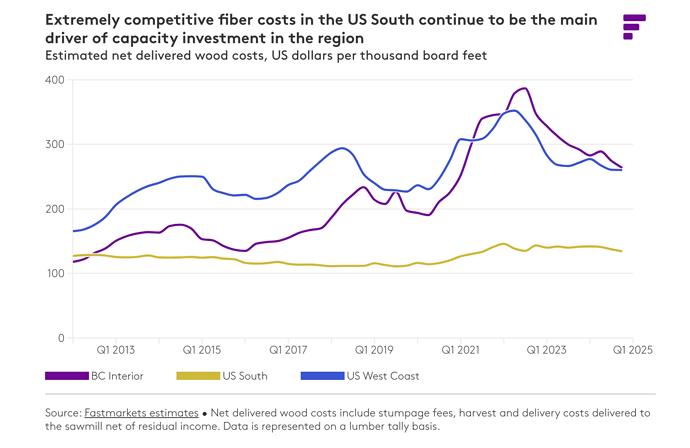

Of course, we cannot ignore the fact we have seen massive investment in Southern Yellow Pine capacity in the US South over the years; since 2015, we estimate the South has added about 8.0 BBF of operable sawmill capacity. Some will point to lumber duties and managed trade in the form of Softwood Lumber Agreements as a critical driver of this investment in the US.

While its certainly true duties, tariffs, quotas and other trade barriers can redirect investment into the domestic market, it seems clear that the bigger piece of SYP CAPEX story is tied to relative fiber availability in the US South. Meanwhile, log supply in British Columbia has become further constrained as a repercussion of the mountain pine beetle kill and policy choices in the province. Much of the sawmill investment in the South would have likely come regardless of trade barriers and helps explain why very little investment has been seen in high-cost producing regions in the US like the PNW. The fiber story cannot be ignored when discussing the rise of SYP in the US South and US production share gains more generally over the years.

The industry speed limit

Finally, even if the US industry is able to conquer all the hurdles laid out above and we get a CAPEX boom to fill the Canadian gap, there’s a pretty clear speed limit to production expansion.

Looking through the reported industry data that we have back to the 1970s, US softwood lumber production growth generally tops out at just 4-5% a year even in favorable pricing environments. Why? Because of all the bottlenecks at the mill and logging levels already mentioned that ultimately restrain the pace of supply growth.

There are a handful of instances where sawmill production has sustainably grown by more than 10% for more than a few quarters, but this has almost always occurred coming out of extremely depressed operating rates of less than 70%. Although market conditions remain soft, the current operating rates remain well above these levels.

Even if tomorrow the US were able to begin the process of actively replacing Canadian supply, with production growth of 10.0% and in 2025 and 7.5% in 2026 respectively, followed by 5.0% in the following years, it would still take until 2029-30 for US production to fully replace Canadian supply. This also factors in US current exports pivoting into the domestic market.

Critically, this also assumes no demand growth over the coming years, which is, of course, a very unlikely scenario given what we know about North America’s housing shortage and the longer-term trend growth in the broader economy. Even assuming modest demand growth over the remainder of the decade, the US would probably require closer to 10 years to completely and sustainably wean itself off external lumber supply.

Conclusion: Canadian wood products supply is not going away anytime soon

Even after years of eroding market share due to both existing countervailing and antidumping duties on Canadian softwood lumber and, more importantly, declining fiber supply in British Columbia, US dependency on Canadian wood products remains quite high, as illustrated above.

Further trade barriers on Canadian supply, which went into effect this week, have sent prices shooting higher to sufficiently cover the cost of new tariffs such that some Canadian supply can be profitably sold into the US market over the medium-term horizon. Again, the US wood products capacity base would need to expand substantially to fill the void of eliminated Canadian supply, and the time frame would certainly be more than a year or two in almost any reasonable scenario.

Keep in mind, the back of the napkin analysis performed here is not considering species substitution challenges or impacts on less commoditized lumber markets where Canadian supply is even more critical to the supply picture, all of which would further complicate a rapid pivot to more US supply. Under the right policy conditions and given enough time, US “independence” from Canadian wood products supply and imports more broadly is a plausible scenario, but clearly comes with distinct trade-offs.

The brunt of the pain over the near term will be carried by consumers as they absorb these higher prices, especially at a critical point when housing affordability in the US is also under a microscope and home builder margins are facing increased pressure. This is one trade-off the current administration will be forced to grapple with in the coming months as concerns about the economy escalate and questions about what will catalyze a rebound in residential construction grow.

In the meantime, Canada will continue to be an important piece of the wood products supply story if the US hopes to address its home affordability problem. While boosting domestic production may be a clear policy objective and a potentially worthwhile goal of the current administration, the data clearly tells us this cannot be accomplished quickly, even with the substantial trade powers wielded by the executive branch.

Source: Does the US really need Canadian wood products supply? - Fastmarkets