Firewood theft: The forests where trees are going missing

By Lyndsie Bourgon1st March 2023

In many countries, poachers are stealing trees from forests in the middle of the night – and the problem may be getting worse. Author Lyndsie Bourgon investigates the complex reasons to blame.

In the stands of oak, birch and beech that populate Germany’s forests, hundreds of trees have been stolen, one-by-one. In one forest alone – Konigs Wusterhausen, near Berlin – poachers took 100 pine trees last winter. In response, a new initiative sprung up to encourage hikers to report sightings of suspicious stumps or people. Managers have begun to nestle cameras into tree branches.

The reason? Wood poachers have been harvesting their winter heat. In October 2022, the Working Group of German Forest Owners Associations (AGDW) reported that firewood scavenging was on the rise in the country’s forests, where people were felling trees and chopping them up for easy transport, or in some cases taking wood that was already chopped down from the side of the road. The AGDW estimated the value of stolen wood from German forests the previous winter had reached into the millions of Euros.

Tree theft has become a global problem. To tackle it, there are now hidden cameras in forests around the world – in the redwoods of California, the foggy coastal forests of the Pacific Northwest coast, and the tropical rainforests of South America and Southeast Asia. All are meant to dissuade poachers, who enter the woods at night and take out valuable, old-growth timber. In my book, Tree Thieves: Crime and Survival in North America’s Woods, I tracked poachers and wood dealers as they tromped through the woods to harvest wood and sell it to artisans, mills, and manufacturers, as well as meeting the park rangers hoping to stop them.

In their most recent figures, the US Forest Service estimates that timber worth $100m(£83m/€95m) is poached from their land each year. In Canada, the province of British Columbia reports that around $20m (£17m/€19m) worth of timber is stolen from publicly managed forests each year. And globally, this trade contributes to the estimated $152bn (£131bn/€149bn) trade in illegal timber on the black market. Each region’s bounty is locally unique: in eastern Missouri, poachers take walnut and white oak; the bark is stripped off elms in Kentucky; bonsai are stolen from gardens in San Diego and Seattle; redwood burl is carved from sequoia in the towering redwoods of northern California.

A redwood stump poaching site in northern California (Credit: Lyndsie Bourgon)

This wood enters our lives in a myriad of ways: during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, the price of wood skyrocketed, and people stole processed timber by the truck-full. Retailers of hardwood flooring and flatpack furniture have been caught sourcing illegal wood in their supply chains. And every winter, parks located in or near cities report the theft of fir boughs and pine trees, felled for Christmas trees.

But the most common motivation identified in my research was to supply firewood. Stories coming from Germany’s forests echo those in my home province, where Douglas fir is often poached near roadways that cut through public conservation land. There’s often evidence that these trees have been cut into blocks right where they fell, then loaded into the back of a truck and driven off. In rural areas, where it’s not uncommon for homes to be heated by multiple stoves as opposed to central heating, this poached wood often feeds the burners in local communities. But now, in the long shadow of both the energy and cost of living crises, the demand for firewood is on the rise. The market for poached wood is expanding.

In the UK, the demand for wood heat has been tangible: wood stove sales have increased by 40%, and chainsaw sales have followed in lockstep. In Dorset, £10,000-worth ($12,000/€11,300) of wood was stolen from a Wildlife Trust site in early January.

Firewood demand in Europe is increasing as gas energy prices rise (Credit: Getty Images)

In the background, firewood prices have increased throughout Europe. In September 2022, the World Economic Forum weighed in, stating that a country’s woodstores are now an indicator of a strong economy. Bulgaria, Switzerland, and Poland all reported that the price of a bundle of wood had more than doubled, and that some people were being scammed into paying high rates for a cord of wood (about 3.6 cubic metres/128 cubic feet) that were never delivered. In Poland, it was reported, officials have begun to consider distributing anti-smog masks in anticipation of people burning wood and trash to find heat.

As I came to know poachers through my research, many of them detailed how they poach wood that they dry to fill their woodstoves, or the stoves of their family members. Some sell their bounty online to needy neighbours, connecting through social media. Outside North America, researchers have found that iconic trees like baobab are being illegally sold and manufactured into charcoal used for cooking.

The ethics of wood poaching have become increasingly complicated: trees that need to be protected to ensure biodiversity, forest health, and climate change mitigation are now being taken by poachers in night-time raids, but this is not necessarily a crime motivated by simple greed. There are economic pressures that exacerbate the problem: poverty is endemic in rural communities that need heat and income. For many poachers, harvesting wood is an act of self-sufficiency, tradition, and necessity. It requires technical skills that had been passed down to them through family members, a “form of osmosis”, according to one.

A Douglas fir poaching site in British Columbia (Credit: Lyndsie Bourgon)

Burning wood for heat is often accompanied by stigma, particularly in urban settings. But wood’s utility morphs along class lines. A crackling fire lit under a glittering mantlepiece at Christmas is aesthetically pleasing and traditional, whereas black smoke spewing from every house in a low-income neighbourhood is often perceived as “dirty”. For many homes, wood and other biofuels (like peat) are accessible and affordable methods of keeping warm during winter, when prices for fuel skyrocket. “There is a real social divide,” says Martin Pigeon, a forest and climate campaigner at the European activist organisation Fern.

Fern’s research has indicated that what was once a supplementary form of heat for many has now become primary, the backup now providing security in a time of energy and cost-of-living crises. “A lot of this is policy driven,” Pidgeon tells me on a winter’s day in Brussels. “If we had a public sector energy supply, it might not be this way.”

Though the impacts of burning wood on health and environment vary depending on the type of stove used and wood burned, there is no doubt that burning wood contributes to air pollution and deposits health-harming particulates that hang in the air every time a stove door is opened and flames stoked. The rise of wood-burning, both at home and in industrial biomass power plants, has the potential to undo progress in air quality improvements over the past century.

In recent reports, Fern and Greenpeace have cautioned that poaching firewood cannot be compared to the damage caused by mass, legalised logging that services the biomass industry, which burns wood to provide energy. Since 2005, according to Fern’s analysis, burning wood has increased alongside the biomass industry’s production – now, more than half of the European Union’s wood harvest is burned. “It put a price tag on trees that previously didn’t have one,” says Pidgeon. “Created an incentive to log the forest.”

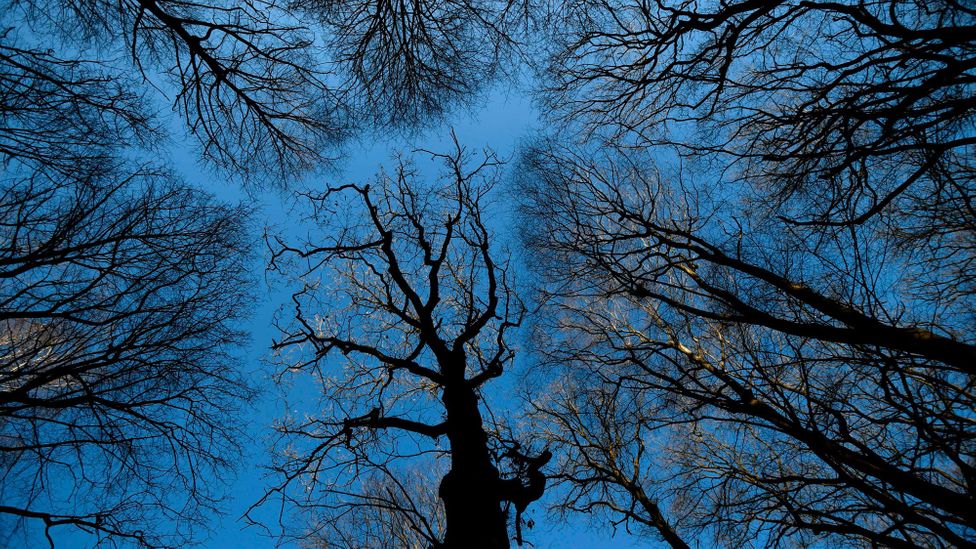

Germany’s forests are losing an increasing amount of timber to poachers (Credit: Getty Images)

In times of energy unaffordability and insecurity, wood is a reliable source for many, both in harvest and use. Energy insecurity remains a pressing concern for Europeans across the board – the End Fuel Poverty Campaign estimated in October 2022 that 7 million British households were in fuel poverty.

In December 2022, for instance, the Shetland Islands off the north coast of Scotland, found themselves without heat sources when a snowstorm cut off power and telecommunication lines to the island. For similar regions, where power outages are not uncommon, wood stoves are a lifeline in the dark and cold. Earlier in 2022, the council in Aberdeen, where the ferry from Shetland docks to the mainland in the north-east of Scotland, instigated a plan to remove fireplaces from council homes, leading to fierce backlash from constituents, many of whom argued that they would be left without a key heat source during power outages. In one media report, Louise Kelly – a resident of the village Braemar, Aberdeenshire – eloquently called her wood stove a “backup for resilience”.

While researching my book, I have heard echoes of Kelly’s reliance on her wood burner from almost everyone I have ever spoken to about managing, harvesting, and living with wood. There is a near universal connection to the burning of wood for heat – and a common thread of safety and subsistence found while sharing a seat around any sort of fire. Firewood, I have come to learn, is imbued with all sorts of meaning, whether domestic, environmental, or political – and this makes the rights and wrongs of tree theft more nuanced than first appears.