Federal agencies are working on a new satellite system for wildfire monitoring designed with fire managers in mind.

The mission, called WildFireSat, aims to enhance fire management in Canada by supplying experts with critical information so they are better able to fight fires and protect communities as well as infrastructure.

In an average year, roughly 2.5 million hectares of forest burn across Canada – a number expected to double by 2050 due to climate change, the federal government projects.

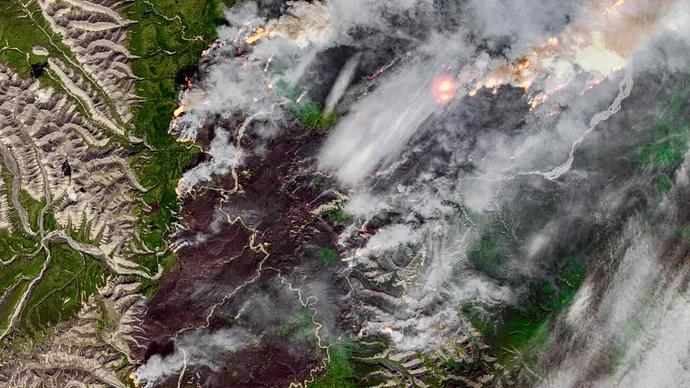

This summer, many Canadians got a stark view into this fire-filled future. In the NWT alone, more than four million hectares have burned, according to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre.

To help fire managers tackle worsening wildfires, four institutions – the Canadian Space Agency, Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Canadian Forest Service and the Canadian Centre for Mapping and Earth Observation – have teamed up to create a wildfire monitoring satellite system built specifically to be used in fire management operations.

The mission is scheduled to launch in 2029.

Although some satellite-based instruments, such as Nasa’s Modis and Viirs, already gather information on wildfires, existing satellite missions generally aren’t tailored for firefighting, said Colin McFayden, of Natural Resources Canada’s Great Lakes Forestry Centre.

Instead, existing satellites largely cater to scientific purposes or monitor weather, McFayden said, leaving gaps in the information that fire managers need.

For instance, McFayden said, satellite data currently isn’t available when fire managers need it most, during the “peak burn period,” when fires tend to be most active.

“That’s around 17:00 local time, give or take, depending on where you are in Canada,” he said.

It’s also right around the time fire managers start to plan for the next day, he said, which might involve looking at where losses occurred, where to deploy remaining resources, or how to communicate with the public about fire danger.

Once satellite data is collected, McFayden said, it also needs to be relayed quickly.

“Even though satellites are up there collecting data that can be used for managing fire, once it gets to be a couple of hours old, in a tactical sense, it really starts to lose its value,” he said.

With WildFireSat, federal agencies plan to collect data around the peak burn period as well as in the early morning, when fire agencies typically adjust their plans for the day ahead, McFayden said. The goal is to get the data into fire managers’ hands within roughly 30 minutes of it being collected.

According to the federal government, information gathered through WildFireSat will be used to characterize a fire’s intensity and rate of spread, two pieces of information useful to fire managers. Data gleaned from the new satellite system will also help to create more accurate air quality forecasts and measure carbon emissions from fires.

The hope is that, with improved intelligence, fire managers will be better informed to make decisions about when to call evacuations, which fires to prioritize fighting, and how best to manage resources, as the Toronto Star previously reported.

By fire managers, for fire managers

From the early stages of the mission, the WildFireSat team has looked to fire managers to inform the satellite system’s design.

A few years ago, McFayden and his colleagues surveyed wildfire managers to find out more about what they need from satellite data.

They asked about the decisions those managers must make, how fast they need to make them, and how old information can be before it stops being useful, McFayden said.

He added that the survey was designed with the help of members of fire agencies, to ensure questions covered the vastly different specialties those agencies include, from people who work in air operations to those with expertise in scientific mapping or putting fires out.

McFayden said he helped design the survey when he was still working in fire management in Ontario, adding that many members of the WildFireSat team are ex-firefighters or fire managers.

Based on the survey responses, McFayden said, the WildFireSat team assessed how they could meet the fire community’s needs given the technology available and associated costs.

Now, he said, discussions are under way about how to best present satellite data to support fire managers’ decision-making.

Preparing for launch

McFayden and his colleagues want WildFireSat to be useful to fire managers, but they also want fire managers to be ready to use it when it launches in 2029.

Waiting for fire management agencies to adopt the technology organically would be “an inefficient use” of WildFireSat’s finite orbit time, they wrote in a 2023 paper.

“There can be hesitancy to introduce new things in fire management if it’s not done in an appropriate manner,” McFayden said. “Because of how high-stakes things are, you can’t have things fail on you when you really need them.”

Although McFayden said fire managers love innovation and are a “wickedly creative” bunch, he said they have to trust new technologies to use them regularly or at a large scale.

“To come in and say, ‘I’ve got something new and you have to use it in a totally different way’ – that takes care and time to do properly,” he said.

To that end, the WildFireSat crew has put together a “knowledge exchange team” to allow the satellite system’s development team and fire managers to learn from each other. Each fire management agency has appointed a “knowledge broker” to the team who knows the agency well, McFayden said.

Not only have these knowledge brokers been informing WildFireSat about questions to ask and who to direct those questions to within agencies, but they also served as points of contact during an assessment of fire management agencies’ readiness to implement WildFireSat in their operations.

The study’s results, which were published earlier this year, found that there is room for improvement in agencies’ understanding of remote sensing, their organizational capacity to integrate new technology, and their IT systems’ abilities to adapt.

In the NWT, McFayden said readiness challenges mostly revolve around limited capacity due to the agency’s relatively small size, though he noted the territory’s strength in information systems and agility in integrating new products.

He described the NWT as one of the heavier users of remote sensing data in Canada, in part due to the sheer size of the area that needs to be monitored for fires.

“NWT has a lot of experience given the remoteness of some areas where satellites are sometimes the only available information,” McFayden wrote in an email to Cabin Radio.

(Cabin Radio reached out to NWT Fire for this article but did not hear back prior to publication.)

The team is now working to create course materials for remote sensing in operational fire management and are in the midst of creating a community of practice, where experts can connect and learn from one another. McFayden said NWT Fire staff are participating in both of these initiatives.

All the while, McFayden said he and his colleagues are continuing to engage with fire experts to better understand their business. Earlier this summer, McFayden travelled to Yellowknife for a remote sensing symposium, where he gave a presentation to a science-minded crowd. He said he also took the opportunity to visit a fire base, to learn about the challenges fire managers are facing, and to build rapport.

Building relationships and being part of the fire community have been integral to engagements so far, according to McFayden.

“It’s a high-trust, high-stakes organization,” he said.

Asked if he thinks the fire management community will be ready for WildFireSat when it launches, McFayden said he is optimistic.

“We’re at this place in time where the technology is available, the willingness is there,” he said.

He added that fire seasons like 2023 drive home the importance of the innovative thinking required in fire management in the coming decades.