As Toronto’s skyline grows, the future of development relies on Canadian forestry

To build better, more sustainable communities and cities, the answer lies in the country’s vast forests. Wood has long been used as a construction material—and for good reason: it’s natural, renewable and increasingly being recognized world-wide as a more sustainable option. Since carbon stays stored in wood products, these buildings continue to serve as carbon sinks long after the wood used in their construction has left the forest. As our schools, seniors’ residences, community centres and city halls take shape, they can also help create the carbon storage needed to meet net-zero carbon goals in the form of beautiful buildings.

“We are still building. We have a housing crisis. We have to change our fundamental practices,” says Carol Phillips, Partner at Moriyama & Teshima Architects. “Why not use renewable materials that can be sustainably harvested and actually pull the carbon out of the atmosphere?”

Mass timber construction can be completed 25 percent faster, reducing carbon pollution during construction by up to 45 percent and it requires less energy to heat and cool long-term. By adopting a zero-waste approach and using every part of the harvested tree, the Canadian forestry industry is converting materials that would otherwise be considered wood “waste”—such as chips and sawdust—into the biofuels that will help reduce our country’s reliance on fossil fuels.

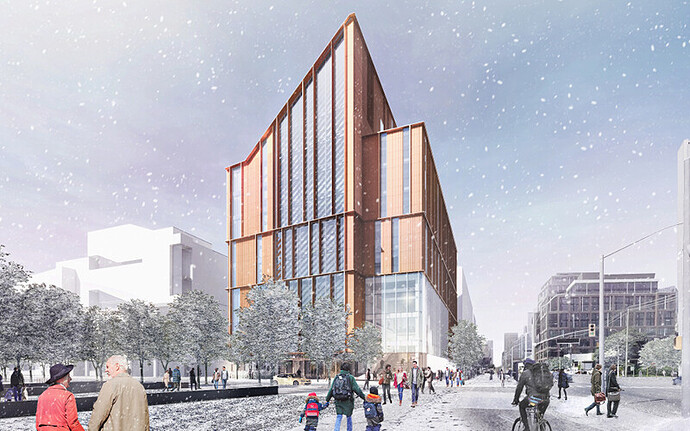

Take, for instance, the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation (OSSTF) headquarters, which is a mass timber project that is currently under construction. Its architecture prioritizes wellness at every level: natural daylighting and fresh air is abundant, solar heat gain and glare is minimized thanks to large overhangs, and a rainwater harvesting system is used for toilet flushing and irrigation. There’s also a green roof, rooftop solar PV panels, and automated daylight dimming to maximize energy savings. The building’s structural components will feature Canadian-sourced mass timber where possible, and will demonstrate a smart, modern and innovative application of natural materials.

In addition to creating more sustainably-built communities, increasing the use of wood in construction would provide numerous economic benefits, including the creation of 50,000 new jobs between 2018 and 2028 in the manufacturing, design, and construction sectors. It would also add $7.5 billion worth of economic activity through the construction of 900 new commercial, residential, and institutional wood buildings in Canada.

“The movement right now towards considering mass timber has everything to do with the fact that it is a renewable resource, and it is designed by nature to be a carbon sink,” says Phillips. With over 20 years of working in Canada and abroad, Phillips has led some of the Toronto firm’s most valued civic, cultural and educational buildings. She brings a passionate drive for powerful and graceful architectural solutions, including George Brown College’s Limberlost Place in partnership with Acton Ostry Architects.

The 10-storey tall wood, mass timber, net-zero, low carbon building is an expansion to George Brown College’s waterfront campus and will be the first institutional building of its kind in Ontario. Toronto and Region Conservation Authority is also turning to mass timber for their new headquarters with a four-story cedar-clad building that aims to be one of the most energy-efficient commercial mid-rise buildings in North America. On the other side of the city, the Scarborough Civic Center Branch stands as the 100th branch of the Toronto Public Library—and it’s most innovative, designed to provide a sustainable natural oasis in a dense, urban environment.

“What I love about designing and building with wood is that it really connects you to the properties of the material itself,” says Phillips. “It really makes you think about the source material—how it was grown, where it was grown, the context—and it sequesters carbon in the body of the material.”

This content was created by The Kit; Forest Products Association of Canada funded and approved it.