B.C. has been fortunate. Stunning mountains. Temperate weather. Natural resources. Outdoor lifestyles. Peace and good order. People from around the world eager to be here.

It’s as if we have become entitled to that sense of abundance, thinking neither ourselves nor our leaders need to make trade-offs to ensure economic well-being for all.

Article content

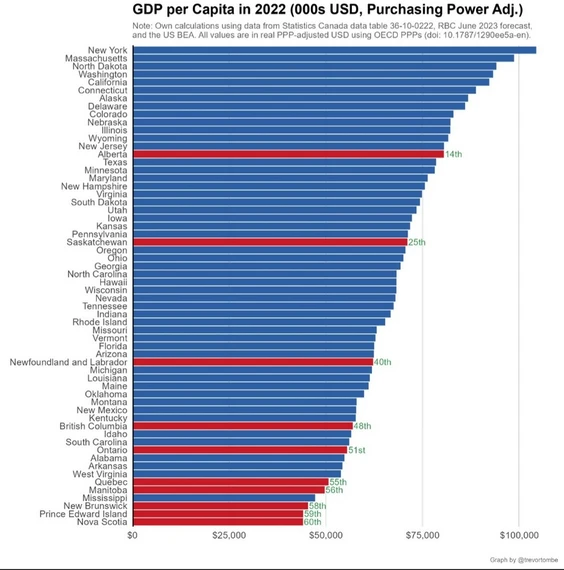

Alas, that attitude is leading to B.C. falling behind. B.C. now ranks a disturbing 48th out of the 60 states and provinces of North America in terms of gross domestic product per capita, one of the best measures of a standard of living. The province’s economic pie is shrinking.

Article content

B.C. has been infected by the national fiscal disease. The Bank of Canada’s Carolyn Rogers warned last week of an “emergency.” Productivity is down to where it was seven years ago. Except for Saskatchewan and Alberta, Canada is not doing well compared to the U.S.

David Williams, senior policy analyst for the Business Council of B.C., says the B.C. government’s own projections for annual GDP per capita come in at $53,500 for 2027 — which is $300 below 2019. With its latest spend-and-borrow budget from February, Williams says, the province faces an “eight-year recession.”

University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe, co-director of the Finances of the Nation website, says B.C.’s economy is doing unusually badly, given we’re considered a “rich” province. The private sector is in retreat.

B.C. needs to either “immediately” raise taxes or cut spending, Tombe says, to bring its debt under control. If the private sector does not produce more revenue, he calculates Victoria needs to double its personal income tax or triple its sales tax for long into the future.

“There has been almost no private sector job growth in B.C. since 2019,” says Williams. The only sector where jobs are significantly expanding in Canada and B.C. is in government. The private sector is stagnant or worse, making things especially bleak for young people.

Where does hope lie for real economic prosperity in B.C.?

Urban British Columbians tend to put faith in high technology, public services and the cool film industry as the foundations of a cleaner economic future. But what about the resource sector — forestry, mining, oil and gas, agriculture and fishing?

Politicians have also been lulled into self-satisfaction by the out-sized housing sector, which has expanded to respond to about 100,000 newcomers each year arriving as a result of international migration. Williams questions the way Canada, particularly B.C., depends on “record immigration levels to turbocharge population growth and housing demand.”

Along with realigning migration levels with the province’s “absorptive capacities,” Williams says B.C. has to re-examine taxation rates. “B.C. has the fourth highest top personal tax rate among the 60 U.S. states and Canadian provinces.” That, he says, scares away high-skill workers and entrepreneurs.

Don Wright, who retired as head of B.C.’s civil service in 2020, also believes B.C.’s economy leans too heavily on new arrivals to “buy real estate and support consumption with income earned elsewhere.” It creates the illusion of a healthy economy. But it has elevated house prices to among the highest in the world. And it’s not sustainable.

Article content

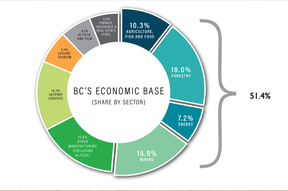

The resource sector still accounts for roughly half of B.C.’s economic base. Source: Framework for Elevating British Columbians’ Standard of Living; Economic Plan 2019-2020. B.C. government.

Here’s Wright’s surprising rundown on the promise and pitfalls of various B.C. sectors:

Film industry

“Everybody loves Hollywood,” says Wright. But B.C.’s film industry, while employing tens of thousands of people, is so heavily subsidized that it ends up not producing much net revenue per employee for government coffers.

Tourism

A tourism industry adds economic diversity, says Wright. “But it tends to offer low wages and it also tends to be fairly seasonal.” An average salary in accommodation and food services is one third that of a salary in mining, forestry, and oil and gas.

High tech

This much-talked-about sector has promise, but there is a particular challenge facing B.C. and the rest of Canada. Although there are many excellent startups, it is often difficult for them to reach world scale while staying anchored here. Young tech companies are often acquired by larger foreign-based companies, which can mean their valuable intangible assets — intellectual property and trade secrets — will be owned and generate returns to other jurisdictions.

Manufacturing

Article content

This supposedly boring industry is more important than people think, says Wright. Focused primarily in the Fraser Valley, it’s producing innovative products, including clean technology, and decent wages.

‘Gateway’ sector

Unrecognized by most, airports, marine ports and railroads account for about 14 per cent of B.C’s economic base, according to analysis by the B.C. government. “They generate quite a lot of jobs and many of them are quite high paying,” says Wright.

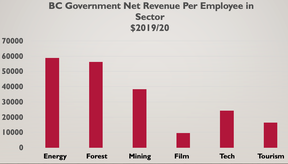

B.C.’s resource industries produce far more “net revenue per employee” for the government than tourism and the film industry. Based on BC Ministry of Finance 2019-20 data.

Resources

This has been and remains the heavy hitter for B.C., like it or not. Residents of the province, especially in the Interior, are suffering because the resource sector is not getting the backing they need, say Williams and Wright. Resources still account for 51 per cent of B.C.’s economic base.

While forestry, mining, oil and gas, and fishing are often targeted by environmentalists, regulators and city dwellers, Williams and Wright note they put far more money into tax coffers per employee than the film industry, tourism and even high tech.

The B.C. government received on average $50,000 to $60,000 in net revenue per employee in the energy and forestry sectors in the 2019-20 fiscal year. That compares to just $16,000 per tourism employee and $9,000 per film industry employee.

Article content

“We’ve got to stop demonizing these industries,” says Wright. “They still have the potential to contribute disproportionately to the standard of living of British Columbians.”

Furthermore, B.C.’s resource sector can be a key to First Nations reconciliation. Natural resources industries will continue to be the dominant economic base for most regions outside the urbanized areas in the southwest corner of the province.

Virtually any new major resource development will involve a substantial partnership with the First Nations in the particular region where that development occurs,” says Wright.

Those who might oppose such projects “will essentially be telling First Nations in remote parts of the province that they don’t have the right to a higher standard of living,” says Wright. “I don’t think that’s going to be tenable.”

It’s time for British Columbians to think more realistically about the economy in order to achieve better standards of living for more people.

We have little to lose but our naivete.