James MacDonald / Bloomberg / Getty

“This is a supply-side problem. This is unlike any other market that any of us lumber traders have ever experienced.”

Last year, lumber turned into the surprise superstar of the U.S. economy when it briefly outperformed bitcoin, gold, and the S&P 500 to become “the hottest commodity on the planet.”

Now it’s happening again. Yesterday, the market closed at more than $1,200 per thousand board feet, a surge in price with only one precedent in the decades-long history of lumber trading. Last year, I wrote about the role that climate change was playing in the lumber volatility. Its effects now seem even more pronounced. “The lumber price story is really a climate-change story,” Stinson Dean, a lumber trader in Colorado, recently tweeted. He has argued that climate change has all but dictated the ongoing price rally, going so far as to call the lumber price a “climate price.”

To learn more, I talked with Dean, who sells to lumberyards from New Jersey to Texas. Friday was the “the busiest day of the year selling lumber,” he said. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Robinson Meyer: Can you start by describing just what a lumber trader does?

Stinson Dean: I buy lumber from the producers, and I own it for three or four months. A lot of that time is spent getting it produced, and moving it on a railcar from Prince George, British Columbia, to Dallas or Atlanta. And I make money when someone needs spruce inventory tomorrow.

Traditionally a lumberyard is my customer. But with how crazy these markets are, you know, people are looking for lumber everywhere. So if you need to buy it, chances are, I’ll probably sell it to you.

Meyer: Can you bring us up to speed with what’s happened in the lumber markets since the beginning of the pandemic?

Dean: We set a new all-time, record-breaking high [for lumber] in August 2020—it just wasn’t making the news yet. Then we started a climb from Thanksgiving 2020 to May 2021. The price of lumber kept climbing, climbing, and climbing, until it got to be a little over $1,700 per thousand board feet. I would seriously equate this to $17 [a gallon for] gas.

But then the whole thing fell apart over the summer [last year]. It took less than three months for it to drop*.* We got in the 400s briefly, but quickly rebounded and kind of chopped around $500 to $700. It started to go up again the week before Thanksgiving. And now … we’re within striking distance of the all-time high again. We’re trading at $1,300. It’s crazy, crazy, crazy.

Meyer: What had the historical price been? On average.

Dean: Four hundred! The old rule of thumb when I got into the business is: You buy below $300 and you sell above $400.

Meyer: This has been a really bizarre time for markets everywhere—with the labor shortages, the variants, the supply-chain issues. Why are you so sure climate change is playing a role here?

Dean: In the business, we call it fiber supply. It’s the lack of fiber, wood fiber, in Canada.

The vast majority of homes in the U.S. are built with Canadian lumber. And British Columbia, Canada, is the No. 1–producing region*.*

So in 2009, 2010, the beetle-kill infestation—the mountain pine beetle—devastated Canadian forests. The beetles come around every year, but it did not get cold enough for long enough, too many years in a row, and too many survived. Beetle-kill lumber has a blue stain in it. For a while, almost every two-by-four seemed to have the blue stain. You can Google it—“blue stain” was a decorative theme for a while because it kind of has a cool look to it.

You’ve got to harvest the beetle-killed trees before they rot, so they’re still viable to be a legitimate structural piece of lumber. So the Canadian government opened up logging aggressively, and—this is an important vocabulary word—opened the annual allowable cut, the AAC. The AAC has impacted what we’re going through now more than any single government policy, including federal interest rates.

So they aggressively logged to capture all the beetle-kill trees. A lot of that lumber went to China—China was the biggest demand for all raw materials coming out of the recession. It’s not like we could’ve left the trees standing and wait for the housing market to recover.

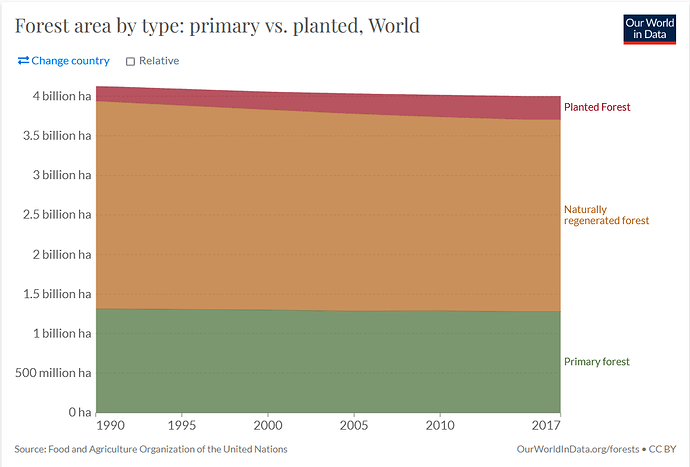

But you can’t cut all the trees, so now there’s a huge fire risk. There are forest fires every year in Canada. That’s expected. But the fire season in 2017 and 2018? Combined, those two fire seasons burned more hectares in British Columbia than in the past 20 years combined.

Meyer: And were they tearing through beetle kill?

Dean: The beetle kill made it worse. It was like kindling.

Meyer: What’s happening to the AAC now?

Dean: The AAC is why we have higher lumber prices, because the Canadian government owns 99 percent of the land up there. So the annual allowable cut was reduced below pre-beetle-kill levels in 2015. And ever since then, Canadian mills have been consolidating—there’s not enough wood for them all to survive.

When I got into the industry coming on 10 years ago, Canadians kept telling us, “We can’t sustain U.S. home starts.” And I kept thinking, That’s the Canadian sawmills talking their position. If we get to $500, $600 prices, there’s plenty of wood out there, and you’re going to start chopping it down, because those are great returns.

Lumber producers are not a disciplined bunch. Whenever we got above $500, they would turn it on and we would go back to $400 or less. Like, every time. So in August 2020, we were all waiting for that—it’s going to $500, $600, $700, and I’m looking around going, Hey, guys, where’s the production? And we’re going to $800, $900.

So I started tweeting: This is a supply-side problem. This is unlike any other market that any of us lumber traders have ever experienced, where mills always had the capacity to just overproduce. I became a full believer in the fact that these mills are at capacity.

Meyer: You mentioned that climate change contributed to the current rally, too?

Dean: The week of Thanksgiving, British Columbia had an atmospheric river. Typically it’s snow. But they had counter-seasonal, torrential rain in Vancouver and up into the lumber-producing region. And when you have fires, you don’t have soil control, so now you have erosion—and when it rains, you have mudslides and floods.

And that is what started the second lumber rally. I think the second lumber rally was inevitable, but this started it early. You could pinpoint the bottom and the reversal in price to the pictures and the headlines of the flood. It destroyed not the trees, not the sawmill operations, but the infrastructure to get the lumber to market.

Your guide to life on a warming planet

Discover Atlantic Planet, a new section devoted to climate change and the ways it will reshape our world

And that’s a problem if you’re in Atlanta. Because you bought that lumber expecting it to get to you in six weeks, and now it’s stuck. Stuff that was bought in November and supposed to ship in November, I’m just now getting shipment notifications. So we’re 10 weeks behind.

Now, British Columbia is not the only lumber-producing region. Other regions have been able to profit off its plight. But there’s just not enough wood to replace British Columbia being completely cut off in the marketplace.

So I said on Twitter, the lumber price is a climate price. And the lumber-price story is a climate story. If we had the beetle-killed trees still here, and our rail lines didn’t get washed out, sawmills would be able to treat this market just like they did in 2006. The price would never get over $500, because they have all the capacity they need.

I think the best comparison is how many homes we completed at the peak [of the last housing boom] and how many we complete now. In 2004, 2005, we completed 2 million homes a year. Now we’re completing 1.3 million homes a year. The price of lumber has tripled, but we’re producing 40 percent less homes. Something’s wrong.

Meyer: The classic explanation of inflation is too many dollars chasing too few goods. Usually, we say, okay, the Fed should raise interest rates and pull some dollars out of the system. But if climate change is causing a scarcity of goods, is raising rates going to help? Are there policies that would be helpful?

Dean: Raising interest rates will blunt demand for housing—no doubt. But if you blunt demand enough to bring lumber prices down, you’re destroying the economy. For us to have lower lumber prices, we can only build a million homes a year. Do you really want to do that? No. Raising rates doesn’t grow more trees.

So the problem, when I look at it, is, how do we increase supply? Well, let’s look at sustainable forest practices, culling, opening up national forests to strategic logging. We have natural resources in the Pacific Northwest that we haven’t tapped since 1993. And we have to sustainably log that; it’s actually dangerous not to. We have an overabundance of southern yellow pine trees that are not used to build homes. Can we improve the way we process southern yellow pine so it [can be used for home building]?

If we’re so dependent on Canadian lumber, what can we do on the margins to change building codes for the lumber we do have? Building codes require lumber with different strengths. The further north you go, trees grow stronger, because it’s colder and the rings are tighter together. Can we look at some Canadian species other than the spruce? Can we use ponderosa pine from Washington? Building codes are local, so it’s a big decentralized issue.

Lastly, we put a tax on Canadian lumber as it comes across the U.S. border. I don’t think if you just eliminated the tax tomorrow, prices would come down. But it would allow prices to get lower when lumber is cheap.

Meyer: Thanks so much. Is there anything else we should talk about?

Dean: Volatility is what makes markets. Extreme volatility, what we’re experiencing, breaks markets. It’s broken the supply chain. You can’t forecast [prices]. When it comes to lumber, climate change has manifested itself in extreme volatility, lack of supply, and a paradigm shift in how lumber markets have behaved for decades. Lumber prices are the second highest they’ve ever been, today, this moment—ever. And it was precipitated by mudslides, which was precipitated by burning, which was precipitated by beetle kill. There’s an infrastructure story in there. There’s a climate story.

Robinson Meyer is a staff writer at The Atlantic. He is the author of the newsletter The Weekly Planet, and a co-founder of the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic.