As Forest Fire Season kicks off… can we all agree that Forest Land Firefighter are some of the most badass people on the planet?

Fun Fact. If you’ve heard about David Goggins, then you should know he’s out there right now digging trenches & stopping forest fires. Why is he there? Because it’s some of the hardest work on the planet.

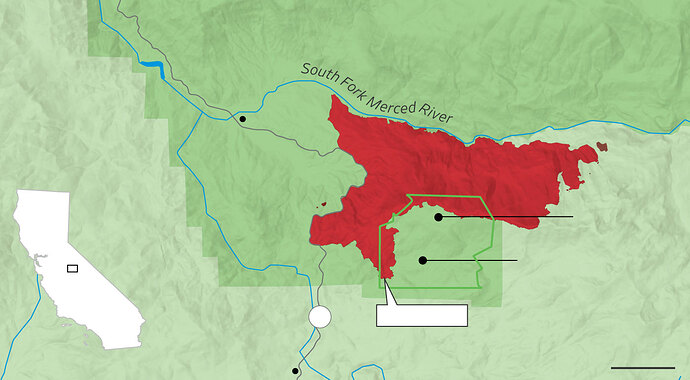

With the Washburn Fire at 25% containment as of Monday, the famous giant sequoias of Yosemite National Park’s Mariposa Grove have seemingly been spared the worst, according to Yosemite forest ecologist and firefighter Garrett Dickman. And while the trees aren’t entirely out of the woods yet, so to speak, Dickman told SFGATE he’s optimistic that the beloved giants are poised to survive.

“The grove itself right now seems to be in pretty good shape,” said Dickman, who on Sunday surveyed the western part of the grove, which was also the eastern flank of the Washburn Fire. “I walked through all the parts that burned and did not see any mortality. … Some of the trees had some burn on them, but the level of burn was well within their ability to to handle it.”

Mariposa Grove is one of Yosemite’s prime attractions, with more than 500 mature giant sequoias stretching up to more than 200 feet high and dating back over 2,000 years. The grove was first set aside in 1864 by President Abraham Lincoln as part of California’s first state park.

Left: A sprinkler system wets the grizzly giant. Right: An air tanker passes above a giant sequoia during the Washburn Fire.

Courtesy of Garrett Dickman/NPS

Dickman confirmed that flames have not reached several of the most famous trees — the Grizzly Giant, the Clothespin Tree, the California Tunnel Tree and the Fallen Monarch. A sprinkler system was put in place to protect the Grizzly Giant and also the Galen Clark Tree, which was named for a 19th century conservationist and stands in the northeastern part of the grove.

“The Galen Clark Tree is most certainly going to be in the fire footprint,” Dickman said. “But based on the level of effort that firefighters were putting into it yesterday, I’m pretty confident it’s going to make it.”

What’s saved these trees, Dickman said, is simple: fuel reduction treatments.

“The really obvious takeaway is we’ve been preparing for this fire for 50 years. And that preparation is saving these trees,” he said. “We haven’t had to wrap trees or really put firefighters at tremendous risk. They’ve been able to engage safely because those fuel reduction treatments have proven to be so effective.”

The Washburn Fire emits a column of smoke from within Yosemite National Park near the Mariposa Grove.

Courtesy of Garrett Dickman/NPS

In recent years, Dickman has been on the front lines when it comes to giant sequoias and wildfire. He aided in last-minute preparations and surveyed the damage in Sequoia National Forest before and after the 2021 Windy Fire tore through Long Meadow and Starvation Creek groves, killing dozens of giant sequoias. The same year, he was also on the ground in Sequoia National Park after thousands of giant sequoias were incinerated by the KNP Complex Fire.

The difference between mass destruction of sequoias in those wilderness areas and the relatively intact Mariposa Grove is instructive, Dickman says, because it shows us that these ancient trees need our protection. That’s something new, he said.

Because of climate change, fires in California are igniting more often and burning hotter than ever before. And thanks to a century of fire suppression, combined with drought, wind events and a bark beetle epidemic, the fuel loads in California’s forests are sky high.

Before these conditions occurred, fires swept through the region’s forests with some regularity, but they didn’t usually burn hot enough to do long-term damage. “Sequoias don’t die very often,” Dickman said. “Their background mortality rate is about 0.1% per year.”

Firefighters prepare giant sequoias for fire by removing fuels from the bases of trees.

Courtesy of Garrett Dickman/NPS

There was a drought in the late 1200s, he said, in which some giant sequoias died in high severity fires. A few more died in 1986 and ’87 fires. But starting in 2015, things got much, much worse.

Some 100 giant sequoias died in and around Sequoia National Park during the Rough Fire, and then in 2017, two fires killed about 120 trees. In 2020, an estimated 7,500 to 10,600 large giant sequoias were killed by the Castle Fire, then the following year another 3% to 5% of the world’s population of giant sequoias died from the Windy and KNP Complex fires.

“So we go from fire almost not ever killing a giant sequoia to it just wiping out 20% in two years,” Dickman said.

While the situation in the Mariposa Grove is mostly under control, the Washburn Fire continues to burn hot just outside of its boundaries, where in certain areas, there hasn’t been fire on the ground for 130 years. In some places, the flames are up more than 200 feet high, and intense enough to lift tree debris hundreds of feet into the air. When the fire is that large, crews can’t get close, Dickman said.

Smoke from the Washburn Fire fills the sky around Yosemite National Park, in California, on Monday, July 11, 2022.

As temperatures climb and the weather becomes more dry, it’s difficult to predict what the fire will do next, and it could reenter the grove from the north. But suppression efforts are concentrated there, Dickman said, including large air tankers, helicopters and six hot shot crews.

Dickman is hopeful that the grove will remain largely unscathed, and that the magnificent trees will be on display for future generations. But he offered some advice for people who have never seen the world’s largest trees.

“I’m an eternal optimist, but there are things that are happening, they’re just moving faster than any of us imagined,” he said. “The thing I tell everybody is, go experience giant sequoias now.”