From the trees and into the forest

By Don Shultz

June 3, 2022 | 2:58 pm CDT

Musings on the future of the wood industry.

No. 1: An unamusing musing

The venerable idiom reminds us of making the distinction between the trees and the forest. Idioms are useful tools of language, and now seems a good time to be reminded of what may be out of our sightline.

An economic environment swollen with demand and fat with synchronous opportunity is counterbalanced by a past that suggests the industry companies may indeed be unable to see the forest for the trees, leaving one wondering how the wood product manufacturers in North America will evolve.

A look back over twenty years reveals the U.S. wood furniture and cabinet manufacturing industry is in a persistent, inexorable decline. By almost any business measure, the industry seems to be disappearing without the will to reverse the trend.

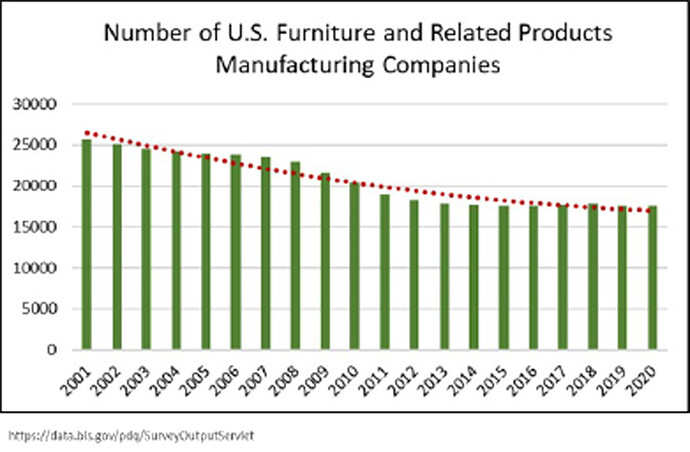

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the furniture and related products sector (NAICS 337) lost nearly one-third of its manufacturing companies since 2001. Indeed, between 2001 and 2020, the industry lost 8,054 domestic manufacturing businesses – without the slightest hint of altering its direction.

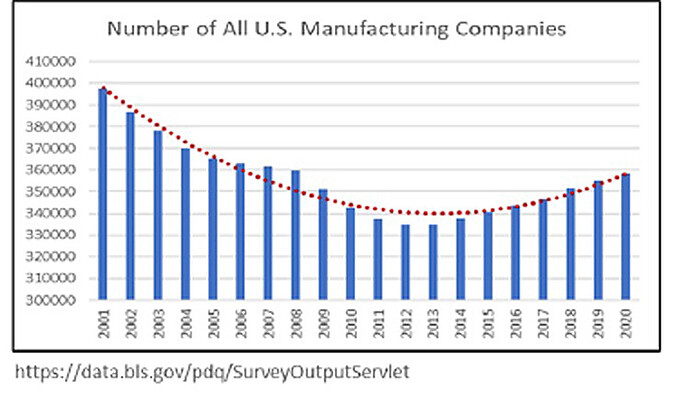

By comparison, a look at all other manufacturing sectors combined reveals two interesting differences. The manufacturing industry in its entirety has fared much better in terms of net lost businesses and recovery.

While across all manufacturing sectors, 39,280 companies were lost; that loss was less than 10% of the total. The losses for wood industry companies were at a rate three times higher than that of non-wood manufacturers.

From its lowest level in 2013, non-wood industry manufacturing companies added 23,531 new businesses between 2014 and 2020 – reversing the earlier trend – regaining about 60% of the companies lost.

During this same period, the wood industry lost an additional 208 firms. An already small domestic industry contracted even further. Today there remain only 17,864 woodworking companies in the U.S., a sector that numbered over 32K companies in the mid-nineties.

As one might reasonably expect, as the wood industry declined, so too did employment. Between the years 2007 and 2020, employment dropped from 515,764 to 329,925, a loss of 165K factory and office workers. This again accounted for about one-third of the total 2007 workforce.

In total during these same years, the wood industry lost over $16 billion in manufacturing revenues. The offshoring of casework and furniture that began in the mid-1990s continued throughout the next twenty-five years, unabated.

Given the recession of 2009 and the pandemic a decade later, some measurable contraction is understandable. Yet, the furniture and cabinet industry has fared far worse than other manufacturing sectors and has not yet recovered.

Clearly, other manufacturing sectors are recovering when the wood industry is not. Why does the wood industry continue to contract when the past several years have seen record demand for the products they manufacture? Why has the deterioration of the sector gone unnoticed and unabated for over twenty years?

Perhaps because we have failed to see all the unhealthy trees in our forest.

The descent of the industry is a harbinger of both loss and renewal, following the path of the perfect bell curve of business-life cycles. Attrition will ebb and flow as existing firms adapt, and new ones innovate in perhaps what may become a kind of wood industry renaissance.

While the numerous symptoms of the decline are conspicuous, the disease cannot be treated until the causes are in plain sight and fully understood. But first, to be clear: one cause was and is not the lack of demand that has remained in relative abundance across the years.

Some will point the finger at foreign competitors; low wages, currency manipulations, dumping. Yes, these are present, but are only tokens of the truth. If this were the case, European manufacturers would not be able to ship fully assembled, high-quality cabinets to the U.S. and sell them at competitive prices.

Germany has among the highest wages and structural costs of western nations, yet kitchen cabinet manufacturers like Nobilia are enjoying great success in carving out their share in the North American market.

Old school’s out

No, the demise of wood industry companies was driven not as much by external forces as by internal ones – internal to the individual companies lost over the years.

Indeed, as Shakespeare reminds us, “the fault… is not in our stars, but in ourselves.” It is not the destiny of an industry to fail, but the failure of industry leaders to manage their own destiny.

Business owners and leaders bear the ultimate responsibility for the success of their companies. This musing was not written for those who have fallen short of that responsibility. For them, school’s out. Rather, what follows is for those who intend to vigorously manage their stars. Since the position of the stars won’t change, we must reposition ourselves.

With some behaviors as old as the stars being blamed for the failures, leaders will create enterprises that no longer resemble the craft-based businesses of our past, but ones that give rise to a neo-industrial era that does not simply embrace technology, but in fact one in which companies’ fulfillment process is de-signed upon it and the customers they serve.

While many of the leadership behaviors of the past will necessarily dissolve, the principles of entrepreneurship will endure. Critical thinking, acute peripheral vision, creativity, integrity, awareness of emerging technologies as well as their market impacts, and a deep unwavering commitment to customers and markets. Most importantly, they will possess the common sense and business acumen to access them by way of strategic differentiation.

These are the attributes of leaders on the new competitive frontier. The familiarity and comfort of traditional business models and the customers they serve will give way to businesses whose processes are interwoven to those of the source of demand. As is always the case, it is the thinking that precedes the doing that will separate those that grow and prosper from those that don’t.

In an industry characterized by sameness, one might argue that the commonalities between the companies was, in and of itself, the most conspicuous cause of failure. In other words, because our companies lacked differentiation, they also lacked competitive advantage.

If all companies are the same, none is unique. Consider for a moment, the current competitive landscape: we produce similar products, run the same machines and software, hire from the same pool of workers, use the same materials and hardware, and make the identical claims of quality, reliability, and customer commitment.

It is largely a statement of fact that many industry companies are precisely equal in the lack of differentiation. Same, same, and more of the same. We are left with only one point of differentiation: price, and more squarely, low price. If you chase the bottom, that’s where you end up. And that is where many industry companies have ended up and why some remain destined to fail.

If there is a leadership behavior that has contributed more to business failures and the decline of the industry, it was (and remains for many leaders) ignorance of the absence of competitive differential that is conspicuous to its customers.

The declining number of industry companies and the consequent loss of industry revenues stands as a stark testament to our failure to understand and adapt to an evolving global market space that was driven by competitive fitness and conspicuous differentiation.

Understanding the past

Success is never the result of anything other than competitive performance. In any aspect of life, success usually expresses itself as a measurement of our competitive performance. Consider the following example:

The wood industry invests in capital improvements (as a percent of revenue) at par with all other manufacturing sector companies. Indeed, with respect to cost structures, the wood industry compares proportionately to all other manufacturing industries when considering expense and investment ratios.

Yet, when considering the average revenue generated per full-time employee, in 2020, the wood industry produced less than one-half that of all other manufacturers: $197,182 per FTE compared to $459,920 respectively. The difference in performance here is pro-found, and the question is again – Why?

The answer lies in productivity. A closer look reveals that while the wood industry has invested equally in capital equipment (as a percent of revenue) when compared to all other manufacturing industries, the results with respect to revenue productivity differ dramatically. Capital equipment investment on average amounts to 1.7% versus 2.3% for the wood industry compared to all manufacturing industries.

As with machinery, software investments in software technologies are comparable when considering the spending as a percent of revenue. In the end, neither machinery nor software investment has brought the wood industry to comparable levels of revenue-generating performance.

Perhaps a more precise metric would be the amount of revenue generated per dollar of payroll invested. Here again we see similar ratios; The wood industry in 2020 generated $7.02 of revenue for each dollar of payroll expense, while all manufacturers averaged $13.04 – nearly double.

Therefore, investments in material assets alone have demonstrated over the past two decades that although necessary, they have been completely inadequate in terms of creating more productive, and consequently more successful, companies.

The data suggests that investment in hard and soft technologies alone is not the arbiter of competitive fitness and sustainable growth. This insight is not based on 2020 only, but looking over nearly a twenty-year period. The ratios gathered over that period are approximately the same.

Positioning for the future

If investment alone isn’t the determinant of competitive performance, then what is?

Few would argue that chess is a contact sport unless you’re playing a friend of mine who occasionally becomes quite animated over my careless decisions. We all recognize chess is primarily an exercise in thought, the chess pieces themselves being the metric of competitive thinking.

For the wood industry, the new competitive frontier lies not primarily in the physical realm, but one which increasingly exists in the world of ideas and thought. Awareness, understanding, foresight, creativity, analytical thinking, and strategy – these are the non-material assets required to create real competitive advantage with respect to performance.

Successful companies will invest in ideas. They will invest in thought. They will invest in understanding the evolutionary shifts in markets. They will adapt and invent new business processes and products to maximize access to new opportunities and customers.

The industry will adapt, it will renew, reconfigure, and rebuild. The real winners will focus on differentiation and productivity. Abundant opportunities will result from creating precise alignment and automating the business process between the source of demand and fulfillment. Bridging the gap between architectural design and production will increase speed and accuracy of project deliveries. Offsite and modular construction will profoundly reshape product management, procurement, and installation, driving design and manufacturing still closer together into a unified workflow. Traditional models for manufacturing, distribution and business will be replaced by new ones driven by the industry’s thought leaders.

All these changes will drive productivity, which will take on newer and broader meaning as leaders extend their intellectual reach beyond the factory floor to include their clients’, but also architects’, owners’, and developers’ business needs.

In our next installment, we’ll drill down on the problems with productivity in the wood products manufacturing industry and consider more closely the performance differences between the wood industry and other non-wood manufacturers.

On the horizon

The U.S. furniture and casework industry stands before an opportunity the likes of which it has never seen. The goal cannot be survival. Rather that it thrives and prospers as it has never done. While none can predict the future, there are some industry partners that take a longer view than most wood business owners.

German board and panel manufacturer Egger Group recently began production at its new $700 million plant in North Carolina. This was not a bet. It was a thoughtful investment in the future of the industry in North America. They see something here that perhaps we yet do not…opportunity.

Now is the time for industry leaders to step back from their trees and begin to see and understand their businesses in the context of the forest.