A $28 billion merger in 2023 created Canadian Pacific Kansas City, connecting Mexico, the U.S. and Canada

Railroad boss Keith Creel drove a shiny ceremonial spike through the track in Kansas City, Mo., last year to celebrate a $28 billion deal that forged the only freight railroad that directly connects Mexico, the U.S. and Canada.

Affixed to his gray-striped suit was a lapel pin with the flags of the three nations.

His corporate creation, called Canadian Pacific Kansas City CP -1.10%decrease; red down pointing triangle, or CPKC, operates a 20,000-mile network stretching from Canada’s ports on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts through Midwest rail hubs such as Chicago and down to factories and seaports in Mexico.

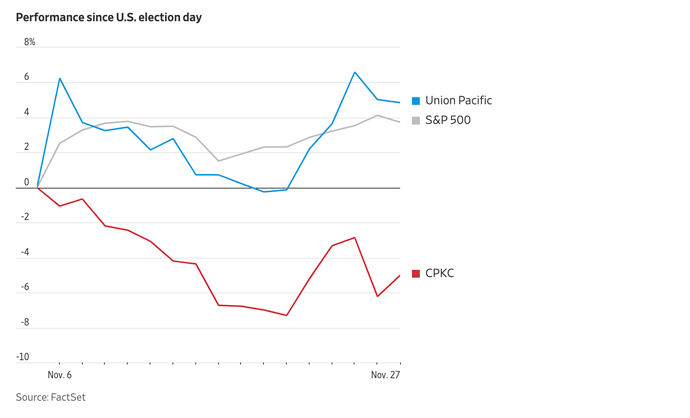

The railroad is the ultimate bet on the promise of the free flow of goods and a key cog in an intricate supply chain that underpins North American trade. It is a bet that suddenly got a lot riskier. Donald Trump’s election victory sparked a small selloff in CPKC’s shares and the president-elect’s threat last week to impose new 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada further spooked investors.

Creel and his executive team have spent recent weeks trying to reassure shareholders that the incoming Trump administration won’t disrupt CPKC’s business and that the logic of its network still holds. Hedge-fund manager Bill Ackman, a major CPKC investor, has also sought to tamp down the fears.

CPKC rail network

Note: Includes rail segments CPKC does not own but has rights to use.

Source: CPKC

Emma Brown/WSJ

The week after Trump’s election, Creel took the stage on Nov. 15 at an industry gathering in New York City to make his case. He said that nearshoring activity in Mexico since the pandemic cannot be easily undone and that CPKC’s network creates new business opportunities for customers.

“These three countries have never needed each other more,” said Creel, 56 years old, who has spent three decades in the railroad industry and has run Canadian Pacific Railway since 2017. The Army veteran got his start as a ramp manager at a rail yard in Birmingham, Ala., before climbing the executive ranks as a proponent of precision scheduling, first at Canadian National Railway then at its in-country rival.

Creel described a possible round trip that a railcar makes on its new network. Diapers are loaded in a railcar in Toronto, which then travels to Texas, “a growing population center,” he said. The railcar is then filled with cotton and taken to textile mills in Mexico, where it is loaded with TV sets or dishwashers that can be brought straight to Toronto, where it is reloaded with cereal and taken to Port Saint John in Canada.

CPKC says most of the goods that it moves from Mexico into the U.S. are produced in Mexico, rather than imported from another country. Photo: /Bloomberg News

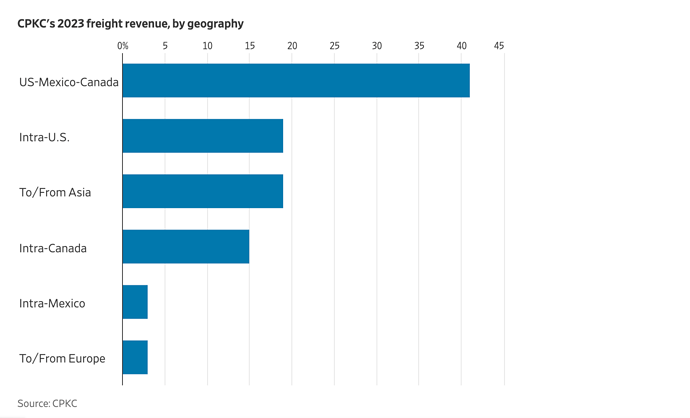

Such cross-border cargo movements made up 41% of the company’s freight revenue this past year.

Each of those steps, however, would get more expensive if Trump makes good on his promise to impose new tariffs on America’s neighbors. And the movement of freight trains through the U.S.-Mexico border has also been cited by Trump as contributing to the flow of illegal immigration.

In 2023, the U.S. intermittently closed rail crossings at Eagle Pass and El Paso, Texas, because of a migrant surge that overwhelmed officials at the Customs and Border Protection agency.

Jason Miller, a logistics professor at Michigan State University, said he doesn’t expect freight companies that have forged stronger cross-border connections to walk away over the uncertainty triggered by new tariffs. “If you’re considering Mexico, you’re doing so because of labor,” Miller said. “A 25% tariff is not in any way, shape or form going to make the U.S. market where you decide to put that production.”

Besides, Miller said, the threat of tariffs may simply be a negotiating tactic. “I quite frankly don’t know how many people are really taking the president-elect seriously on this,” he said.

Ackman has been saying something similar. The billionaire, whose investment firm Pershing Square owns around a 1.6% stake in CPKC, said he remains optimistic about the prospects of the railroad in an investor call on Nov. 21.

“I think he’ll [Trump] be sophisticated in how he uses the negotiating power of tariffs to maximize U.S. interests. But I think the overarching goal here is economic growth for the country,” Ackman said.

Tariffs on goods from China imposed by Trump in his first administration, a new North American free-trade pact in 2020 and the pandemic-induced nearshoring boosted business for North America’s freight railroads.

Between 2018, when Trump introduced tariffs, and 2023, freight flows between the U.S., Canada and Mexico rose 28% by value. The amount moving on railroads increased 17% over the same period. Railroad executives have said they are keen on taking more market share from trucks, which carry about two-thirds of the freight between the three countries.

Union Pacific, another railroad with access to Mexico through six gateways on the southern border, said it would be able to handle any disruptions in supply chains. “We’ve repeatedly demonstrated our ability to respond to dynamic shifts in demand,” said a Union Pacific spokeswoman. Shares in Union Pacific are up about 5% since Trump’s win.

After Trump’s election, the Mexican government pledged to invest $2.7 billion to expand the Port of Manzanillo on the Pacific Coast. That port connects to Mexican railroad Ferromex, which is partially owned by Union Pacific.

The project, expected to be completed by 2030, would add container terminals that would double the port’s capacity to 10 million containers annually by 2030. That expansion would propel Manzanillo to par with the Port of Los Angeles.

CPKC has been preparing to expand its main link into Mexico, which currently carries about 24 trains daily. It is building a second international railroad bridge across the Rio Grande at Laredo, Texas. The $100 million bridge, whose construction started in 2022 and is expected to be finished later this year, will boost capacity on the current single-track span.

CPKC says most of the goods that it moves from Mexico into the U.S. are produced in Mexico, rather than imported from another country. In 2023, CPKC moved 83,500 carloads imported through the Port of Lázaro Cárdenas, about 200 miles south of Manzanillo, making up 1.8% of its total carloads. Most of these loads remained in Mexico.

“While there was rhetoric and headlines, ultimately free trade in North America increased significantly during the first Trump term and a new free-trade agreement was established,” said Patrick Waldron, a spokesman at CPKC. “Since the pandemic, investment in nearshoring in Mexico has accelerated, as has trade between the U.S., Mexico and Canada.”

Trump dismantled the North American Free Trade Agreement and his administration crafted a new trilateral trade deal, the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA, which formed the basis of the 2023 railroad merger. The two railroads were involved in the initial USMCA discussions and CPKC will be actively engaged on these issues again, Waldron said.

In an interview in 2021, when Canadian Pacific won a bidding war for Kansas City Southern, Creel said he expected more shippers to shift from clogged U.S. ports to less-busy ones in Mexico. And he said the combined CPKC would boast “a network that will never be replicated.”

Liz Young and Costas Paris contributed to this article.

Write to Esther Fung at esther.fung@wsj.com