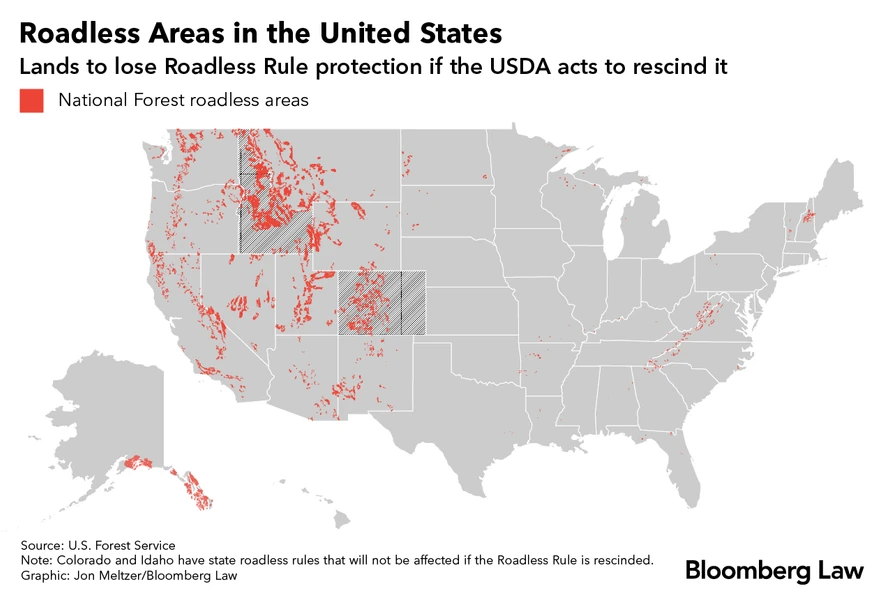

The Trump administration wants to scrap a rule that protects tens of millions of acres of national forest from road-building and large-scale logging—but its zeal to log will face a reality check from government downsizing, possible litigation, and even a soft timber market.

The US Forest Service, which manages roadless areas, is grappling with budget cuts and staffing shortages. At the same time, environmental groups are already gearing up for legal battles, arguing the so-called Roadless Rule safeguards endangered species, clean water, and biodiversity.

“The administration can sprint and rescind the Roadless Rule, but then what?” said Murray Feldman, partner at Holland & Hart LLP in Boise, Idaho. “It seems like a moonshot to try to reverse decades of national forest management plans, rules, framework, and direction by revoking one specific set of rules. But we’ll see.”

The rule that then-President Bill Clinton implemented in the final weeks of his term was envisioned as a way to protect endangered species and 350 watersheds within national forests used for drinking water from Alaska to Puerto Rico.

Among the places the rule has preserved are parts of the world’s largest coastal temperate rainforest in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, vast mountain ranges in central Idaho, the peaks and plateaus above Utah’s contested Bears Ears National Monument, and the Appalachian forest in Virginia.

President Donald Trump’s Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins slammed the Roadless Rule this summer as “absurd” and said it violates the Forest Service’s “mandate” to produce timber. She declared a timber emergency to “get more logs on trucks” and comply with Trump’s March order calling for expanded forest-cutting to avoid importing wood products and reduce wildfire threats.

Adding pressure, the Big Beautiful Bill passed by Congress in July mandates that the Forest Service increase US timber sales by 250 million board-feet each year through 2034. That’s an 8% annual increase based on the 3 billion board feet sold in 2023, and a roughly 75% cumulative spike in logging over the next nine years, according to figures from the Government Accountability Office.

Ben Burr, executive director of the Blue Ribbon Coalition, a motorized outdoor recreation group that joined past lawsuits opposing the rule, said the West is too vulnerable to wildfire and too much land is at stake to be subject to a single administrative rule.

“If we need those areas to be roadless, Congress can do it,” Burr said.

Critics contend the potential damage from revoking the rule, including to water supplies, far outweighs the claimed benefits. This week, 154 conservation groups called on Congress to preserve the regulation and permanently ban logging in more than 58 million acres of roadless areas.

The rollback of the Roadless Rule is expected to affect about 44 million acres—roughly equivalent to the size of Missouri—because Rollins said in June that separate rules protecting about 13.5 million acres of roadless areas in Idaho and Colorado would remain in place.

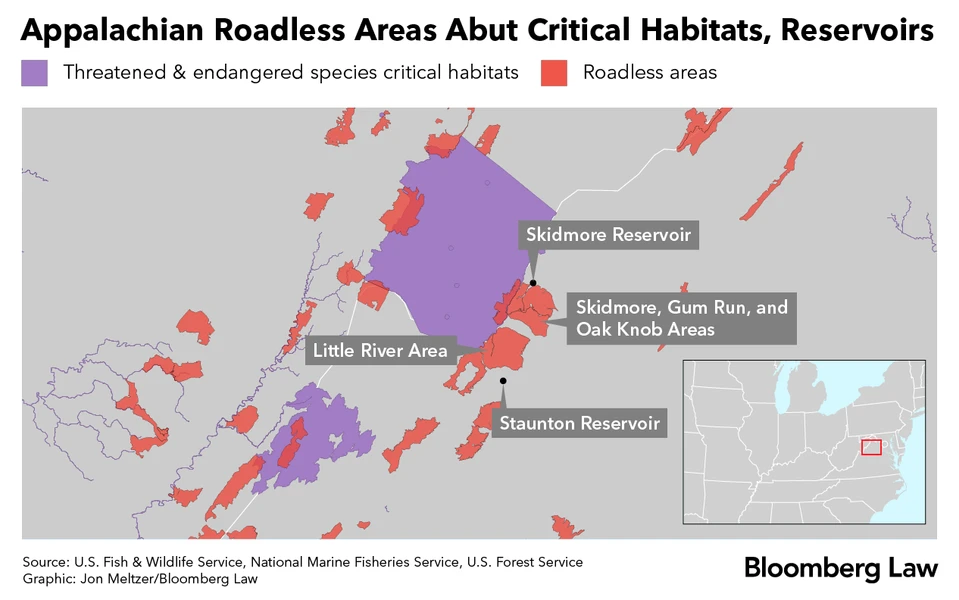

“Roadless areas are the best of what’s left of our national forests,” said Lynn Cameron, a Shenandoah Valley Appalachian Trail maintenance volunteer who’s lobbying Congress to leave untouched George Washington National Forest woodlands that protect watersheds serving the Virginia cities of Staunton and Harrisonburg.

“Municipal water that comes from roadless areas is surface water,” she said. “That’s the cleanest water there is.”

The Forest Service hasn’t taken any official steps to rescind the Roadless Rule since Rollins announced the administration’s intent in June.

The agency didn’t reply to requests for comment about its timeline, but in an emailed response to questions about the impact in Virginia, it defended rescinding the rule as “critical for forest health and public safety” to avoid “delayed emergency response.”

‘Lack of Markets’

Forests in the Pacific Northwest will be the timber industry’s most likely first target if the Roadless Rule is rescinded, said Tim Preso, managing attorney at Earthjustice, who has litigated the Roadless Rule for decades.

The industry isn’t universally agitating for access to roadless areas, though it backs some Trump deregulation moves. Some industry boosters say they need access to roadless areas to reduce the threat of wildfire, mainly in the West.

Pacific Northwest forests are already zoned for logging, and many of them avoid roadless areas for now, said Travis Joseph, president and CEO of the American Forest Resource Council, a trade group representing timber companies in Oregon, Washington, and surrounding states.

“There are no specific areas within the Northwest that we are focusing on if the Roadless Rule is rescinded,” he said. “We are not saying, ‘Go into all these areas and start logging.’ It’s really about what makes the most sense, where’s the opportunity for ecological restoration?”

East of the Mississippi, many roadless areas are in hardwood forest, where there is little immediate demand for timber.

“I don’t imagine there’s going to be a huge amount of interest,” said Terry Lasher, executive director of the Virginia Forestry Association. “Right now, it’s lack of markets. We’re not successful in competing for our export markets.”

That’s especially true for hardwoods. China is traditionally the biggest market for hardwoods but isn’t buying from US companies these days, he said.

There’s also the cost. Timber companies often pay to build new roads to access remote timber stands within national forests, according to the GAO. Once they’re built, the maintenance tab is on the Forest Service.

A proposed 27% cut to its road budget is expected to hamstring the agency’s ability to maintain a 370,000-mile road network that’s already long enough to stretch around the globe more than 14 times.

“The USFS simply does not have the money to embark on a road-building bonanza to attempt to meet the administration’s clearly arbitrary and aspirational timber targets,” said Susan Jane Brown, principal attorney at Silvix Resources in Oregon, a nonprofit environmental law firm focusing on federal forest law and policy.

The Forest Service proposed to slash its budget by 63% in fiscal 2026, and at least 7,500 employees have reportedly already left the agency amid federal layoffs.

The agency didn’t respond to detailed questions about its budget and staffing challenges. Its budget request says some of the revenue the agency receives from additional timber sales under Trump’s logging order will offset cuts, allowing it to maintain existing roads and rebuild old ones.

Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins called the Roadless Rule “absurd.” Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

Moving Fast

The move to repeal the Roadless Rule is just one pillar in the Trump administration’s effort to use emergency orders to systematically dismantle environmental safeguards under the National Environmental Policy Act and Endangered Species Act.

“The overall picture looks like clearing away the Roadless Rule at the same time they’re also trying to lower the bar for environmental analysis that has to precede logging projects,” Preso said.

Preso was on the team that successfully defended the Roadless Rule in court, first when Wyoming brought a lawsuit challenging the rule, and then when George W. Bush administration’s tried to replace the national rule with one that allowed the Forest Service to create a roadless plan for each state.

Ultimately the rule was upheld and reinstated in 2011. State-specific rules apply today only to Idaho and Colorado.

Because the Forest Service hasn’t taken any official steps to repeal the rule, Earthjustice is in a wait-and-see mode on legal challenges, Preso said.

Burr said the Blue Ribbon Coalition would try to join any lawsuits defending the decision to roll back the Roadless Rule.

Quickly Open to Logging

Beyond court action, steps that could slow or prevent preserved areas from being quickly opened to road builders and logging interests in some areas could hasten them in others.

Lifting the rule puts decision-making about logging and wildfire mitigation into local forest managers’ hands instead of blocking forest access at a national level, said Joseph, from the American Forest Resource Council.

“We believe rescinding the Roadless Rule should be about giving land managers greater flexibility to reduce wildfire threats where fire-prone forests and communities intersect,” he said.

That’s already true in Wyoming, where the US Forest Service asked state foresters to help manage national forests in the wake of federal worker layoffs, said Kelly Norris, the Wyoming state forester.

However, Forest Service research published during the first Trump administration shows that more wildfires ignite near roads, wildfire mitigation efforts have been more common in roadless areas than in the rest of the national forest system, and roadless areas have no effect on wildfire burn rates.

Joseph said many roadless areas will remain protected because activities there are governed by the local forest management plan that’s in place. A sizable number of those plans respect roadless areas, especially if they were written in the last 20 years, he said.

But at least half of national forests are managed under plans that don’t protect roadless areas, said Sam Evans, an attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center.

“Even where forest plans look like they are as protective as the Roadless Rule, they really aren’t,” he said. “The roadless rule is a national-level backstop against messing around in roadless areas.”

Some forest management plans predate the Roadless Rule and allow for logging in roadless areas. Some plans were written during the George W. Bush administration and didn’t account for the Roadless Rule; those roadless areas would lose protection and can be managed under their previous plans, Evans said.

That’s true for some national forests in Wyoming, including some that are ailing and need to be actively managed to protect watersheds, Norris said.

Rescinding the Roadless Rule “will allow us to manage our forests in the way we agreed to originally,” she said, and set up the state’s watersheds for “true health.”

Water Quality Concerns

In Virginia, the Forest Service acknowledged many roadless areas won’t be open to loggers anytime soon because the George Washington National Forest is managed under a 2014 plan that will continue to protect them.

That hasn’t eased long-term concerns that some roadless areas could eventually be open to loggers and road-builders and threaten water quality in the Shenandoah Valley.

Virginia’s largest roadless area protects part of a watershed that Staunton, Va., uses for drinking water. A nearby complex of roadless areas protects part of the water supply for Harrisonburg, Va. Together, more than 75,000 people live in the cities that rely on the two water systems.

Though there is no immediate proposal to log those roadless areas, if protections are lost, new roads and logging steep slopes will eventually harm drinking water quality, said Bradley Striebig, an engineering professor at James Madison University, who co-wrote Harrisonburg’s environmental action plan.

That’s because logging and roads will allow sediment, debris, and pollutants to wash off newly-logged denuded slopes and into drinking water reservoirs, increasing water filtration costs, he said.

“We know that trees will be harvested, water will become more polluted,” and it will become more expensive for cities to operate their drinking water systems, Striebig said.

Staunton officials didn’t respond to requests for comment. But in its latest water quality report, the city cited the Forest Service’s strict development controls around its George Washington National Forest reservoirs as one reason for its good water quality.

Harrisonburg officials declined to comment because they don’t know enough about how the Roadless Rule rescission will affect them, a spokesman said.

Skidmore Reservoir in Virginia’s George Washington National Forest is surrounded by land protected under the 2001 Roadless Rule. The reservoir supplies drinking water to Harrisonburg, Va. Photographer: Bobby Magill/Bloomberg Law

Some Shenandoah Valley residents say support for roadless areas and pristine forests is widespread and bipartisan.

“We view the mountains as a resource we want to protect,” said Emmet Hanger, a retired Republican state senator. “We take it as a given here in the valley that those mountains are almost sacred. You don’t go up there and mess around, you manage them appropriately.”

Cameron, a retired librarian and conservationist, talked to Bloomberg Law one hazy late July day standing near 4,397-foot Reddish Knob, the summit where Clinton announced the Roadless Rule a quarter-century ago. She pointed to a profusion of monarch butterflies feasting on blooming milkweed, an example of the wildlife habitat she said is incredibly effective at protecting biodiversity and imperiled species.

“Some people don’t realize how special it is,” she said.