Maybe it was Jason Lentz’s genetic destiny — though he certainly fought against it — to become one of the world’s best lumberjacks. His father and his grandfather and his great-grandfather, who had worked the Great Depression-era logging camps in Oregon, were all elite lumberjacks. Or maybe it was because of all that wood he chopped in China. Either way, his story can be said to begin in 1981, when his father, Melvin Lentz, showed up at the Webster County Woodchopping Festival in West Virginia.

After a weekend of wielding his huge seven-pound ax, his six-foot single-buck crosscut saw and his souped-up chain saw, called a hot saw, Mel won the contest. Being a lumberjack, in the woods as well as competitions, was all he had wanted for himself since he was a kid and saw his own father win trophies, and at 21, he was already on his way to becoming the most decorated American athlete in the history of his peculiar sport. That night, at the festival ball, he danced with Liz Sears, who had just been named the event’s Miss Congeniality. Her grandfather started the competition decades before.

Four years later, after their first child, Jason, was born, Mel Lentz and Sears moved to her hometown, Diana, W.Va. Mel tried to push his son into the sport from the time he took Jason as a 2-year-old to the Lumberjack World Championships in Wisconsin’s Northwoods. But Mel soon learned a common lesson: “It’s hard to beat something into a kid if they don’t want to do it,” he told me one morning this past summer. “You always want your son to follow what you’re doing. Sometimes it happens, sometimes it doesn’t.”

And Jason didn’t want to do it. In fact, he hated it. “I didn’t want to be anything like him,” Jason says.

As a competitor, his dad was revered — “the King of the Lumberjacks” and “Mel the King” and “Melvis.” As a father, he was often absent. Jason hated that lumberjacking took his dad away for as many as 11 months a year, barnstorming the country and world in search of competitions and their measly winner’s checks. For nine years straight, Mel spent the winters training in Australia, the center of the competitive-lumberjack world. He could make $500 or $1,000 at a show, but the winnings didn’t amount to much when set beside the cost of equipment and travel. For a time, Mel worked a lumberjack show at Sea World Ohio, while Jason, his mother and his little sister scraped by in West Virginia. Jason blamed the sport for his growing up poor — poor even by the standards of one of the poorest counties in one of America’s poorest states.

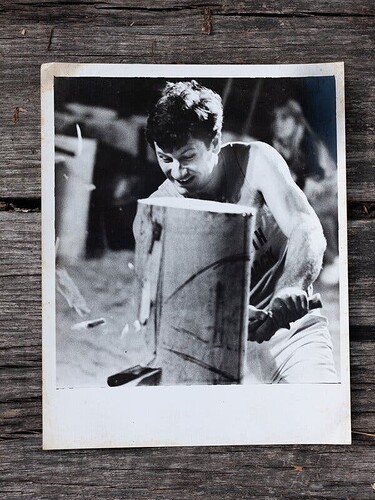

Melvin Lentz, known as the King of the Lumberjacks. He won the Stihl world title six times. Credit…Natalie Ivis for The New York Times

So instead of chopping the wood laid out for him by his dad, Lentz shot hoops on the side of the shed where his dad ground axes. He excelled at basketball, a bruising 6-foot-6 center who led the state in scoring as a high school senior before playing for Eastern Mennonite University, a Division III school in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. He made plans to play basketball overseas. But when the opportunity fell through, he found himself instead making $10 an hour at a lumberyard in his college town, drinking too much, living off the McDonald’s Dollar Menu, getting his electricity shut off, lost. “He just came to a dead end,” Mel says.

Then his father put him in touch with a friend who had a job for Jason doing lumberjack exhibitions at Chimelong Paradise, an amusement park in Guangzhou, China. Reluctant to follow in his dad’s steps but out of options, he flew to the other side of the world. There, out from under Mel’s shadow, Jason Lentz was free to find his own path. It led him right back to his father.

A few years ago, Jason Lentz was visiting his best friend from childhood, Nathan Ezell, and they went to a fantasy-football draft. The toughest guy in Ezell’s small town — 6-foot-2, 260 pounds, unbeaten as a fighter — challenged Lentz to arm wrestle. “And Jason absolutely slammed the guy,” Ezell says. “When he manhandled him — just a slam job, it went that fast! — everyone was like, ‘Oh, my God!’”

Ezell has been in awe of Lentz’s strength since they were Little League teammates. During his childhood, Lentz was known by a nickname partly inspired by his prominent front teeth and protruding ears: Opie. But Opie was no pushover. Ezell had to put a sponge in his catcher’s mitt so that Lentz’s fastballs wouldn’t bruise his hand. “When people meet him, they’re like, ‘Golly, he looks so big and strong,’ and I’m like, ‘He looks strong, but he’s way stronger than he looks.’”

Lentz and other lumberjacks often compare their sport to golf: Power comes from hip torque instead of arm strength; precision comes from producing a repeatable swing.Credit…Natalie Ivis for The New York Times

That brute strength is the advantage that Lentz, who is roughly the size of an N.F.L. tight end, holds over virtually all his opponents in the Stihl Timbersports Series, which are the biggest-money events in the sport. The series began in 1985 as regional logging competitions in the United States and has now grown into national competitions for nearly 1,600 athletes in 27 countries, along with two separate Stihl world-title events. While strength is important, it’s far from the only thing that matters. Lentz and other lumberjacks often compare their sport to golf: Power comes from hip torque instead of arm strength; precision comes from producing a repeatable swing. As in golf, the difference between really good and a champion often depends on mental strength: being able to forget one bad swing and move on to the next. Time in the gym helps, but the best way to train for chopping wood is to chop wood.

The Stihl series, which promotes lumberjacking as “the original extreme sport,” includes six disciplines. The standing block chop simulates felling a tree: Competitors use “racing axes,” specially designed for the heavy but speed-driven chopping of timbersports, to chop through a vertical block of wood. The underhand chop simulates cutting up the felled tree: Lumberjacks stand on horizontal logs and chop them in half. In the single buck — also called the “misery whip,” because an uneven cut can cause the band-saw-like steel to whip back and forth and exhaust the sawyer — a lumberjack slices a slab of wood, or “cookie,” from a horizontal log using a six-foot-long crosscut saw. The springboard chop mimics what loggers do when a tree’s root bases are too hard and thick: Lumberjacks chop two pockets into the wood, insert springboards, climb seven or eight feet off the ground, then chop through the tree. (Lentz can do this in less than 50 seconds.)

A crowd at the 2022 Lumberjack World Championships, where Lentz was defending his title.Credit…Natalie Ivis for The New York Times

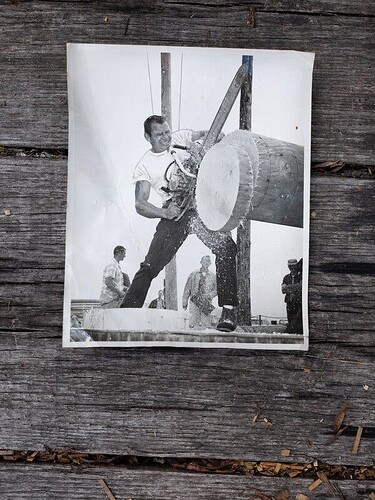

If the springboard chop is the discipline that requires the most familiar forms of athleticism, the chain-saw events are the ones that everyday Americans assume they can do nearly as well as professionals. The stock saw uses a standard chain saw to slice two cookies from a horizontal log. The loudest event is the hot saw, which involves 60-pound chain saws modified with engines from motorcycles or jet skis or snowmobiles to spin the chain at around 13,000 revolutions per minute. When you watch Jason Lentz pull the cord to start his machine, lift his mammoth hot saw into the air, then make three cuts through 20 inches of white pine — down, up, down — to slice three cookies in 6.15 seconds, as he did in last year’s Lumberjack World Championships, you realize that, no, you cannot do this.

Today’s timber industry, highly mechanized, barely resembles the logging camps of the 1800s, but competitive lumberjacks like Lentz are the closest modern-day cousins to the American archetypes of old. In the 1890s, Scribner’s Magazine and Harper’s Magazine published stories about the strong, honest, hard-working men of logging camps, chivalrous toward women and in touch with nature — “gentlemen of the woods.” It was Paul Bunyan, first mythologized in an advertising campaign for Red River Lumber Company, who cemented the notion of the lumberjack as the forest gentleman. For a while, there was another, contrasting type of popular conception as well: “timberbeasts,” the dissolute men of timber towns known for their brothels and bars and violence. Today’s timbersports world requires elements from both types — brute strength of a timberbeast, hard work and mental acuity of a gentleman of the woods — to succeed.

It is man versus nature, both primal and practical: the smell of sawdust and chain-saw fumes and oil.

When Lentz arrived at Chimelong Paradise, China’s largest amusement park, he fit neither mold. He was just an aimless young man with an empty bank account. Part of his job was to play the villain in a water-skiing stunt show; he also took part in a choreographed fight with a woman who grabbed his arm and somersaulted him to the ground. But his main role at the park was to put on exhibitions of chopping and sawing, so he had what would have been an unusual luxury for a competitive lumberjack: an unlimited supply of practice logs.

In his spare time, Lentz did two things: He ate six or seven meals a day, and he lifted weights with an Australian powerlifter named Lee Nagorcka. In college, Lentz was lanky, strong but not fully filled out. Three years in China made him a timberbeast: He gained more than 50 pounds of muscle and returned to the United States weighing 285 pounds.

Sign up for The New York Times Magazine Newsletter The best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week, including exclusive feature stories, photography, columns and more. Get it sent to your inbox.

He also came back as someone he never expected to be — his dad. “Even though they say they’re not, they’re the same, to a T,” says Alicia Lentz, Jason’s sister.

His father gifted him equipment and advice, even if it meant hollering over the roar of Jason’s chain saw. That presence was not without its drawbacks, though: the pressure, for instance, that comes with being the son of perhaps the best-ever at their shared vocation. “His body size is intimidating, his name is intimidating,” says Erin LaVoie, one of the world’s top female wood-choppers and Lentz’s former partner in Jack and Jill events, in which a man and a woman each work one side of a double-buck saw. “Not many people can be that type of athlete, and he also knows how to make his gear perform well.” She then adds a more cautionary note: “But Mel is going to point out what he’s screwing up, and as a son who needs the love of a father, it’s hard. Every person should have love from their parents, Mel just gives it to Jason differently. He doesn’t pat him on the back and say ‘Great job’ as often as Jason needs. They both love the sport, and they both do it their own way.”

Lentz built a practice space at his West Virginia home, in a remote valley a half-hour from the nearest Wal-Mart. Nowadays, friends who visit are greeted by his golden retriever, Jack the Ripper, and the sight of 60 or 70 wood blocks, peeled and ready to chop. “Once he came back home, he was full-bore,” Mel Lentz says. “Now a D10 bulldozer couldn’t stop him.”

The Lumberjack World Championships take place every July at the Lumberjack Bowl, a 5,000-person-capacity outdoor stadium in Hayward, Wis. Hayward is in the cutover, an area in northern Wisconsin not far from Lake Superior that was cleared by commercial loggers in the early 20th century. Logging is still an ongoing concern here, but Hayward, a lakeside town of some 2,500 people, has morphed into a year-round tourist destination. The Fresh Water Fishing Hall of Fame is home to a 500-ton, 143-foot fiberglass muskie, which is said to be the world’s largest fiberglass sculpture. The Moccasin Bar doubles as a wildlife museum with dioramas of taxidermied animals: One shows a boxing match between raccoons, with a groundhog as referee; another shows chipmunks drinking, gambling, fishing and yodeling. During the championships, you can buy kangaroo-leather hats and hear the Pinery Boys singing the same tunes that shanty boys, river drivers and sawmill hands sang a century ago in the Upper Midwest.

One appeal of competitive lumberjacking is that the sport derives from a necessary activity — the work of felling trees and turning them into logs — instead of a contrived activity, like putting a ball into a net. It is man versus nature, both primal and practical: the smell of sawdust and chain-saw fumes and oil, the smack of ax against log, the roar of a chain saw that cuts off conversations midsentence. “The more we get disconnected from the things we use, since we’re part of this giant global system, there’s this real appeal to seeing that a dude can still cut the [expletive] out of a piece of wood,” says Willa Hammitt Brown, a historian at Harvard who is writing a history of lumberjacks. “It’s doing a thing!” Or, as Erin LaVoie puts it: “We’re just a bunch of good ole boys who like to get dirty and drink beer.”

On the first morning of this summer’s competition, Lentz was annoyed with his dad. The night before, he had dinner under the frozen gazes of a bear and a 14-point elk mounted on the wall at the Steakhouse & Lodge on T Bone Lane, then returned to his hotel room. Mel’s hot saw was leaking, so he disassembled it in the room they were sharing and fiddled with it for an hour and a half. Once Mel finally fell asleep, he started snoring. Jason had to turn up the air-conditioning full blast to drown out the noise. “Can’t live with it, can’t live without it,” Jason told me the next day.

He was in no mood for small talk. He is generally a pleasant person but not when he’s focused on a competition. His mind is stuck on wood. He’ll talk about his hopes for how his wood’s grain will look, or about his technique on the standing block chop, or about his mistake the weekend before, but little else.

The weekend before, Lentz did not do well at the 2022 Stihl Timbersports U.S. Championships in Little Rock, Ark. In 2021, he established himself as the best lumberjack in the world, winning pretty much every big event, including his first Stihl world title (which his dad won six times). And he started 2022 well, winning in the spring the Stihl U.S. Trophy, a relay-style event, then finishing second in the Stihl World Trophy event in Austria. But in Little Rock, a mistake on the single buck, when his saw got stuck in the log for a couple of seconds, led to a seventh-place finish overall. In Hayward, he was still dwelling on that loss.

‘We’re just a bunch of good ole boys who like to get dirty and drink beer.’

It did not help that his dad sat next to him at every event, his voice cutting through the din with encouragement and criticism. “I can hear him out of 10 million people, just screaming,” Jason told me, as he sat on the tailgate of his Toyota Tundra, whose bed was filled with some $40,000 in lumberjack equipment. “His voice — I hear it, and it takes focus off what you’re doing.”

After the first day, he stood in sixth place in the all-around, but the only thing that mattered on the second day was qualifying for Saturday’s finals. He did so easily, and his dad slept at a friend’s nearby cabin that night so Jason could get a good night’s rest.

For the finals — the arena was packed — Mel’s advice was simple: “You can’t make mistakes today.” Jason could have won the hot saw — he beat the winner’s time by 0.8 seconds — but one of his cuts didn’t completely sever the cookie, a mistake that led to a disqualification in the finals. He finished third in Jack and Jill, second in the double buck, fourth in underhand chop, third in standing chop and fifth in springboard chop. His archrival, Matt Cogar, whose family’s history in the sport runs as deep as Lentz’s, edged him out in seemingly every event. When Mel Lentz won the ax throw during what was most likely his final Lumberjack World Championships (he is 63), Jason wasn’t around to celebrate: He had fled the chopping deck after a lackluster showing in the previous event.

He did win one event: the single buck, with a time of 13.64 seconds, beating his closest rival by nearly a half-second. He raised his fist the moment his cookie dropped to the dock. The feeling seemed more relief than celebration. “Finally did something right,” his dad said with a laugh inside the competitors’ tent, just out of Jason’s earshot.

He finished third in the all-around standings; Cogar, who, like Lentz, calls West Virginia home, finished first. Lentz tried not to let his disappointment show, but he couldn’t shake the feeling. “I know I can be better,” he said later.

After a night of Coors Lights and shots of Fireball Cinnamon Whisky, he picked up the check for his winnings the next day at 9 a.m., then drove off on his thousand-mile trip home. This had been his one week of annual paid vacation from his day job — he works for a company that lays water pipe. During the summers, he is able to drive to weekend competitions on Thursdays by working 11- and 12-hour days the rest of the week to get his hours in. You do not get rich in competitive lumberjacking. (The total annual purse for Stihl’s American competitions is $350,000.) Every lumberjack in Hayward had a day job except Cogar, whose Red Bull sponsorship allows him to focus exclusively on his sport. Lentz supplements his winnings with income from smaller sponsors: Champion Power Equipment, Grizzly Coolers, Freedom Homes, Maxima Racing Oils and Custard Stand Hot Dog Chili, based in his home county. It stinks, he said, always having to say, “Hey, man, can you give me some money?”

Lentz is among the world’s best in both power and precision; his shortcoming, he admits, is speed, something he could gain by competing more frequently — except for that day job. If he could focus solely on the sport, Lentz thinks, he could become the world’s best. So do others. “He’s just a powerhouse, 6-6, just a monster — he’s designed for the sport,” says Nate Hodges, a friend and one of America’s top timbersports athletes. “The only thing taking away from him being the best is he doesn’t have the time to put in the training like Matt Cogar does.” Instead, it has to be a hobby, albeit an all-consuming one, as it was for his dad.

He pulled into his home in Diana at 3 a.m. on Monday. His alarm went off at 5:45 a.m. By 7, he was digging up yards and laying pipe for water lines. By Wednesday, he would be on the road again: a county fair in West Virginia followed by the Woodsmen Show in Pennsylvania and more competitions every weekend past summer’s end.

The year’s capstone event, the Stihl Timbersports World Championship, took place in Sweden in late October. It turned out to be a fittingly melancholic end to Lentz’s disappointing season. He was delayed in London for nine hours. His equipment arrived a day late, so he in turn was late to the training camp in central Sweden, a seven-hour drive from the event in Gothenburg. The training facility was Lentz’s dream: a massive shed with storage space for wood and equipment, a weight room, a training area and a dining area and bunk beds. He practiced with his team, but then Lentz came down with flulike symptoms and couldn’t leave his hotel room on their only down day.

He competed only in the team event, having failed to get the one individual spot reserved for an American male. Though the team managed to produce an upset, beating a strong New Zealand squad and finishing second to Australia in the 20-nation competition, Lentz watched in frustration from the crowd as the single-buck event was won with a time that he felt he could have beat. And his archrival, Cogar, finished second overall in the individual competition.

“Last year wasn’t the fluke — this year was,” Lentz told me afterward. “It’s the maturity thing. It’s like golf. My next 10 years, 13 years — those are going to be my prime.”

He has a plan for 2023. Because his day job is seasonal — there’s no laying water pipe during a West Virginia winter — he plans to head to Australia in January, where he will spend a few months training. He doesn’t need to build strength; he needs speed, so he’ll work on his fast-twitch muscles. He will bring 100 of his racing-ax handles to sell to fellow competitors, and he will stay with Laurence O’Toole, an Australian champion lumberjack, and help with O’Toole’s tree-removal business on the side. “Rest of the time, just training and eating and working out,” Lentz says. “Be an athlete — that’s the dream, you know?”

The Australia portion of his 2023 season will end in April at the Sydney Royal Easter Show, known as the “Wimbledon of Woodchop.” He thinks he has a chance to win the single-buck title in Australia. Only one American has ever won that title in Sydney: Mel Lentz.

“I know I can be better,” Lentz says.