In the Trump administration, trees were crops. In the Biden administration, they’re guardians of the climate.

This fall’s election will determine which label wins, though the Forest Service’s work on the ground may not change all that much.

That’s one conclusion from forest policy groups, which see the rhetoric around managing national forests hinging on the presidential race between Kamala Harris, the Democratic nominee, and Donald Trump, the Republican contender, even as radical changes aren’t likely anytime soon in the 193-million-acre forest system.

There isn’t much controversy over the need to do more to improve the health of the national forests,” said Bill Imbergamo, executive director of the Federal Forest Resource Coalition, representing companies that harvest timber on federal lands. He added, “I don’t see a potential Harris or Trump administration giving up on active management as part of the solution to the wildfire crisis.”

No matter who’s elected this fall, the Forest Service — which is filled from top to bottom with career employees rather than political appointees — will continue to log forests, including older trees in some places. It will plant more trees to catch up with a decadeslong reforestation backlog and allow monitored wildfires to burn in some places, despite scattered but vocal opposition to the policy.

And the agency will likely keep spending more than half of its discretionary budget fighting fires, a milestone first hit in 2015.

That year, the Forest Service predicted fire suppression costs could hit $1.8 billion by 2025. Now, the agency predicts the cost for the coming year could exceed $3 billion.

Lawsuits from environmental groups on large forest projects may not let up much, either. Despite the Biden administration’s stated goal of protecting mature and old-growth forests, the Democratic administration is fending off legal challenges to logging projects on the Daniel Boone, Kootenai and Nantahala national forests, among other places.

The usual battle lines will likely persist no matter who leads the Forest Service. Although the position is a career rather than political post, leadership has tended to change with administrations.

Possibly more important is who the incoming president picks as secretary of the Agriculture Department and how closely the White House inserts itself into forest policy, said Steve Ellis, a former Forest Service and Interior Department official who heads the National Association of Forest Service Retirees.

“Such choices are critical,” Ellis said.

Infrastructure and climate law funding rollout

Much of the Forest Service’s current workload is tied to two big appropriations bills passed during the Biden administration — the bipartisan infrastructure law and the Inflation Reduction Act. The laws poured billions of dollars into forest management, including reducing potential wildfire fuel like dead and dying trees, replanting trees in areas damaged by wildfire, and rehabilitating roads and campsites.

The IRA alone sent $5 billion to the Forest Service. Nearly half of which was devoted for the agency’s state and private forestry programs, including planting trees in communities around the country. About $2.2 billion went directly to national forests, including for forest thinning.

Republicans aren’t likely to cut off money in those areas if swept into power, policy groups said. But they’ll probably be more skeptical than Democratic counterparts about how it’s spent and whether to add still more.

Forest work that Democrats billed as an emergency under those appropriations was slow to start, so the agency’s success in using the IRA and infrastructure funding — which runs out in the next few years — could determine whether Congress provides more money during the next administration, Imbergamo said.

While IRA funds for the Forest Service may not appear in jeopardy, a lobbyist for another advocacy group said, that assessment is “subject to change of course depending on the appetite and margin of victory for the GOP.”

This lobbyist, who requested anonymity to speak openly about offices the group works with, said a rollback of unobligated IRA and infrastructure law funding is a “distant but distinct possibility.”

Forest Service Chief Randy Moore testifies before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. | Francis Chung/POLITICO

The next administration will inherit a shorter-term budget crunch at the Forest Service as well. In June, Forest Service Chief Randy Moore said the agency would curtail hiring for non-fire-related positions and emphasized that future hires through the IRA and the infrastructure law would be considered temporary or term employees.

State forest agencies are pressing Congress to direct more money at programs that benefit them, such as state fire assistance grants in the forest stewardship program, which helps private forest owners manage their land. But proposals in both the House and Senate for fiscal 2025 are millions of dollars behind the recommendations of the National Association of State Foresters.

Some programs, like landscape-scale forest restoration projects, could see a shift in emphasis, said Maya Solomon, senior director of policy and advocacy at the American Forest Foundation.

Democrats would likely push for more money and direct it at climate resilience and ecosystem health, she said, while with Republicans in charge, “Funding might be more limited and directed towards projects with immediate economic or resource management benefits.”

Strategy for mature and old-growth trees

The biggest split between Democratic and Republican control may be on protecting old-growth forests. Neither campaign has had much to say on forest policy, but Harris is expected to build on the Biden administration’s record and Trump is expected to return his first term agenda.

The Democratic Party platform adopted at this week’s national convention in Chicago pledges to “work to reduce threats to iconic old growth forests.”

The Biden administration is in the final stages of preparing a systemwide forest plan amendment to conserve old-growth areas in national forests, including by reducing timber harvesting in some areas. Republicans have roundly opposed the idea, which is all but certain to be curtailed in a second Trump administration.

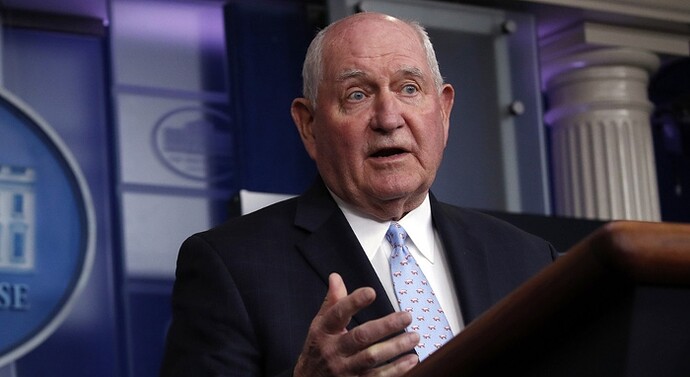

Former Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue. | Alex Brandon/AP

In 2017, Sonny Perdue, Agriculture secretary under Trump, told a House subcommittee that trees are “crops” that “ought to be harvested for the benefit of the American public” — setting early on the administration’s tone on forest policy.

In its proposal on old growth, the Biden administration takes a different tack. Mature and old-growth forests, the Forest Service said, “offer biological diversity, carbon sequestration, wildlife and fisheries habitat, recreation, soil productivity, water quality and aesthetic beauty.”

In reality, timber harvesting remains part of the Forest Service’s mission. And the old-growth strategy asserts that wildfire, pests and disease — not logging — are the greatest dangers to the nation’s forests.

The administration also left “mature” forests out of the amendment, a term that applies to areas with old trees that could eventually become old growth.

The Biden administration has scaled back — but not entirely halted — proposed harvests in old-growth areas while the forest plan amendment is pending. The proposed amendment says old-growth logging wouldn’t be permitted if the main purpose is commercial.

Moore and Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack have said they’re also committed to expanding the use of low-value wood taken off national forests through thinning projects. Possibilities include wood-to-energy projects and new construction techniques.

Disputes about logging in old-growth forests have “never gone away and never really been resolved,” Ellis said.

Some environmental groups, such as the Sierra Club, say they hope a Harris administration would give the forest restrictions teeth. An end to commercial logging in old-growth areas is “the result we want,” said Alex Craven, forest campaign lead for the Sierra Club.

Craven sees precedent in plans like the Northwest Forest Plan, adopted in 1994 to protect more than 24 million acres across 17 national forests in Washington, Oregon and California.

“Our hope is an amendment can be durable,” Craven said.